- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- A Hollywood-Style Escape from Tehran: When a Cover Story Saved Six American Diplomats

A Hollywood-Style Escape from Tehran: When a Cover Story Saved Six American Diplomats

From the 1980 “Canadian Caper” to hostage diplomacy: a long history of tension, silence, and spies.

For twelve consecutive nights, air raid sirens echoed through the streets of Tehran—a capital under attack. The city was struck by Israeli air raids of unprecedented intensity. In two weeks of bombings, according to Iranian authorities, at least 627 people were killed and nearly 5,000 wounded.

The sense that something was coming had already emerged days earlier, when the U.S. State Department ordered non-essential embassy personnel to leave the country.

A signal that immediately evoked a historic precedent: in November 1979, at the height of the Islamic Revolution, a group of student militants stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 52 American diplomats hostage for 444 days.

But during that attack, six American diplomats managed to escape and hide for weeks, until they were exfiltrated in one of the most daring undercover operations of the Cold War, known as the Canadian Caper.

In this issue of Debrief, we tell that incredible story through some of the lesser-known details of a case that became widely known after the release of the fictionalized film Argo.

This issue was written by Sacha and edited by Luigi.

In This Issue of Debrief:

At the Roots of the Hostage Crisis

In February 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned to Iran after fifteen years in exile to lead the final phase of the Islamic Revolution, which brought down Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, a longtime U.S. ally. On April 1, 1979, following a national referendum, the Islamic Republic of Iran was officially declared.

The new theocratic regime viewed the United States as the "Great Satan" and had not forgotten the CIA-orchestrated coup in 1953 that overthrew Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. When the U.S. admitted the ailing Shah for medical treatment that autumn, many in Tehran saw it as a provocation—and the prelude to a possible pro-Western restoration of the monarchy. On November 1, Khomeini accused the U.S. of plotting against the revolution, and three days later, the attack was underway.

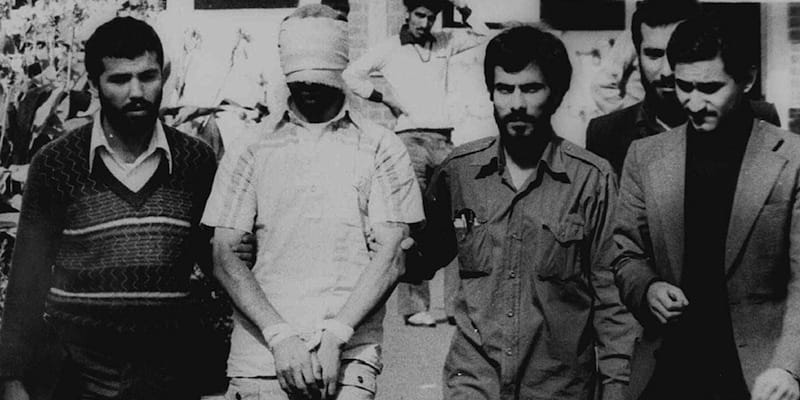

On November 4, hundreds of revolutionary students stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran and took 52 American diplomats hostage. They were blindfolded, paraded on television, and turned into political bargaining chips. The captors demanded the extradition of the Shah, then in U.S. custody, and an immediate end to all American interference in Iranian affairs.

Hostages

For the Carter administration, it was a diplomatic and media nightmare. Every option seemed like a losing one: negotiating with the new regime risked legitimizing it, while a military solution proved disastrous, as the failed Operation Eagle Claw in April 1980 made painfully clear.

The crisis ended only in January 1981, with the signing of the Algiers Accords—just hours after Ronald Reagan was sworn in as president. The agreement included, among other things, the unfreezing of billions of dollars in Iranian assets and a U.S. pledge not to interfere in Iran’s internal affairs.

And yet, amid that global standoff, there was one story unfolding in the shadows: the story of six American diplomats who managed to escape the embassy takeover and leave the country thanks to an undercover operation so improbable it could have been written in Hollywood.

And that’s exactly where this story begins.

Hollywood in Tehran: The Great Escape of the Canadian Caper

When pro-regime students stormed the U.S. Embassy in 1979, six American diplomats managed to slip out through a side exit while their colleagues were tied up and blindfolded by the Revolutionary Guards.

Their names were Robert Anders, Cora and Mark Lijek, Joseph and Kathleen Stafford, and Henry Lee Schatz. They would later become known as the “Canadian Six.”

The six escaped officials

For several days, the six fugitives wandered through Tehran, changing hiding spots each night. A Thai cook from the embassy helped them find makeshift shelters. They had to move during the day, blending into the crowds, because after curfew, any checkpoint could mean disaster.

After six days on the run, one of the diplomats, Robert Anders, reached out to a trusted friend: John Sheardown, a Canadian official based in Tehran. When asked if he could help, Sheardown didn’t hesitate: “What took you so long? Of course you can come over.” That moment marked the beginning of a secret joint operation between Canada and the United States, an operation that would go down in history.

Sheardown and the Canadian ambassador to Iran, Ken Taylor, divided the six Americans between their two diplomatic residences, where they would remain in hiding for 79 days. The Canadians were taking a huge risk: if the revolutionaries discovered they were sheltering American fugitives, the entire Canadian embassy could be stormed, and the staff branded as accomplices to U.S. “spies.”

Ambassador Ken Taylor, meanwhile, continued his diplomatic work as if nothing were happening. He showed up to meetings with the same revolutionary government that was holding his American counterparts hostage, while quietly coordinating secret communications with Washington.

Tensions were sky-high. If the Iranian regime realized that a few Americans were unaccounted for, a massive manhunt would be launched.

That’s when Tony Mendez enters the picture, a CIA officer specialized in covert operations. At Langley, the CIA headquarters, various plans had been under review for weeks. Mendez proposed one so crazy no one believed it could actually work.

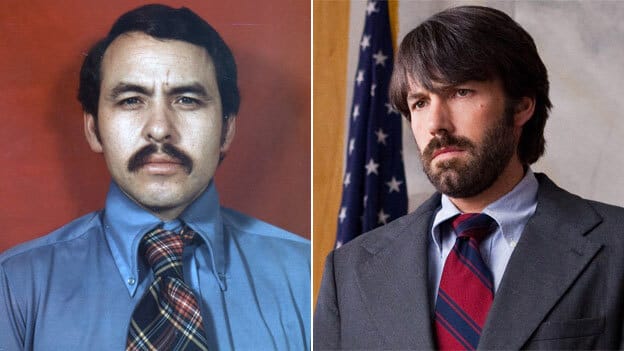

Tony Mendez and Ben Affleck, who portrays him in the movie

The idea was to get the Americans out of Iran by pretending they were a Canadian film crew scouting exotic locations in Tehran for a fictional sci-fi movie titled Argo. It was such an implausible plan that it paradoxically became believable. “I believed we should try to devise a cover so exotic that no one would imagine it was being used for operational purposes,” Mendez later said. And it was clean: no military raids, no gunfire.

Washington gave the green light. “PRESIDENT HAS JUST APPROVED THE FINDING. YOU MAY PROCEED ON YOUR MISSION TO TEHRAN. GOOD LUCK,” read the encrypted message personally authorizing the mission, signed by President Jimmy Carter.

Mendez got to work with obsessive precision. In Hollywood, he recruited a real film makeup artist, John Chambers (famous for Planet of the Apes), and together they built a fake production company called “Studio Six Productions.” They rented actual offices (in the old Columbia Pictures lot) and activated real phone lines, ready to answer any calls about the supposed project. With the help of a few insiders, they placed ads in trade magazines like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, and printed posters and business cards to promote Argo, the fake film styled in a “Middle Eastern aesthetic.”

The plot for Argo was “borrowed” from an actual sci-fi project abandoned years earlier, Lord of Light by Roger Zelazny, carefully adapted to look like a film that could plausibly be shot in Iran. They even included positive references to Islam in the storyline.

The Canadian government issued real Canadian passports for the six Americans, complete with cover identities, a decision approved through a special order by the Canadian Cabinet in a closed session. The Canadians added extra touches: they handed Cora Lijek a fresh copy of Variety featuring the Argo announcement, to show airport authorities if questioned.

Tony Mendez flew to Tehran on January 25, 1980, under the alias “Kevin Harkins,” and before departure he put the six through an intense crash course to prepare their cover. Each of them received a full identity: new names, Canadian nationality, and roles in the fake crew, director, screenwriter, location scout, cameraman. Within 48 hours, they had to memorize every detail. They learned their aliases, made-up biographies, even practiced speaking with a Canadian accent.

To get into character, the six rummaged through the wardrobe Mendez had brought and picked out Hollywood-style outfits. Off came the drab government-worker clothes; on went silk shirts, gold medallions, and ’70s-style sunglasses worthy of a movie producer.

January 27, 1980. Dawn. Everything had been planned down to the last detail. The airline tickets were already booked: Swissair flight 363, departing Tehran for Zurich at 7:30 a.m., with backup seats on later KLM, Air France, and British Airways flights, in case anything went wrong.

Fortunately, the plan to fly out at dawn worked: the airport was nearly empty, and the staff, perhaps, less alert. Mendez arrived first to oversee the check-in. Soon after, the six “filmmakers” appeared together, escorted by a second CIA agent (codename: Julio).

The eight made it past customs. After an hour-long delay, they blended in with other passengers and headed for the gate, boarding passes in hand. Not long after takeoff, the plane crossed out of Iranian airspace. They had made it.

“Even then, we didn’t really celebrate much,” Mark Lijek would later joke, “because for all we knew, the Iranian sitting next to us could be the Tehran Police Chief!”

News of the escape soon leaked to the media, and the “Canadian Six” were welcomed home as heroes. The American public lavished Canada with unprecedented gratitude: Canadian flags waved across U.S. cities, and billboards read, “Thank You Canada!” Unimaginable scenes today, given the current state of relations between the two countries.

The Canadian Parliament, which had kept the operation secret until the last moment, promptly shut down the embassy in Tehran and evacuated its entire diplomatic staff—just hours before Iranian authorities caught on and stormed the (now empty) New Zealand embassy in retaliation.

The CIA’s involvement would remain classified for another 17 years, until 1997, when documents about the operation were declassified, revealing the crucial role played by Tony Mendez and his team. In 2012, Hollywood cemented the legend with the film Argo, which went on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. The movie, directed by and starring Ben Affleck, spotlighted the dramatic airport escape and the CIA’s ingenuity, though it sparked some resentment in Canada.

Even former U.S. President Jimmy Carter later remarked, somewhat critically, that “90 percent of the contributions to the ideas and the consummation of the plan was Canadian,” adding that Canadian Ambassador Ken Taylor was the real hero, while the film “gives almost full credit to the American CIA.”

Hostage Diplomacy

Over the past fifteen years, the detention of foreign nationals has become a recurring feature in Iran. Since 2010, at least 66 individuals holding dual citizenship or Western passports have been arrested, among them academics, activists, businesspeople, humanitarian workers, and many journalists.

The most well-known case is that of Jason Rezaian, Washington Post correspondent, who was held for 544 days and released in 2016 in exchange for Iranian prisoners and a $400 million cash payment. Before him, in 2009, journalist Roxana Saberi, a U.S. citizen of Iranian descent—was imprisoned and released after just over three months. In 2019, Russian journalist Yulia Yuzik was detained, accused, without evidence, of ties to Israeli intelligence. More recently, in December 2024, Italian reporter Cecilia Sala, on assignment in Tehran, was arrested and held for three weeks in Evin prison.

But the repression hasn’t stopped at Iran’s borders. Dissidents, journalists, and members of the Iranian diaspora have increasingly become moving targets abroad. In 2023, Pouria Zeraati, a journalist and anchor for Iran International, was stabbed in London by men connected to an Eastern European criminal network. According to The Washington Post, the attack was part of an Iranian intelligence operation, not meant to be claimed, but to send a “message” to dissidents.

Meanwhile, other files reveal a more subtle front: one of ideological and diplomatic infiltration. A 2023 investigation exposed how Tehran, through a network called the Iran Experts Initiative, cultivated relationships with researchers, analysts, and Western officials, placing regime-aligned figures inside think tanks and government institutions.

It has been a low-intensity spy war, waged by all sides. One striking example is the case of Alireza Akbari: a former deputy defense minister, a respected figure within the top ranks of the Islamic Republic, and, at the same time, a spy working for British intelligence. According to Iranian authorities, he was the one who revealed the existence of the Fordow nuclear site, now one of the main targets of Israeli and American airstrikes. In 2023, he was sentenced to death for high treason and executed.

Now that Iran is once again at the center of global headlines, not because of a hostage crisis, but because of the bombings that struck its capital and reignited fears of a broader conflict, the grainy images of 1979 come flooding back. Every crisis takes a different shape, but certain patterns of power, visible or not, have repeated themselves for decades, up to the bombings of recent days.

Until the next Debrief,

Luigi e Sacha

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at::

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

We've also launched a podcast featuring interviews with the authors of memorable undercover investigations:

👉 https://open.spotify.com/show

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply