- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- Is Every Investigative Journalist an Undercover Journalist?

Is Every Investigative Journalist an Undercover Journalist?

A conversation with Ted Conover, master of immersion reporting

When we think of undercover journalism, we often imagine a reporter pretending to be someone else, creating a false identity, deceiving their subject in order to get the story. But is that always the case? Or is there a more subtle, more fascinating gray area where deception is minimal, but access is maximized?

In this third issue of Debrief, we bring you an exclusive interview with Ted Conover, one of the most influential immersive journalists in the world. Conover has carried out some of the boldest infiltrations ever attempted, from living alongside undocumented Mexican migrants to spending a full year undercover as a corrections officer at Sing Sing, one of America’s most infamous maximum-security prisons. And yet, the most surprising thing about his work isn’t where he’s managed to go, but how: without ever telling a lie.

Today is Friday, May 2nd, and alongside this newsletter, we’re launching the first episode of our new podcast, where you can listen to our conversation, recorded just a few days ago in Ted’s studio in Lower Manhattan:

This issue was written by Sacha and edited by Luigi.

In this issue of Debrief:

A Spectrum of Deception

“Anyone who's done investigative reporting knows that you don’t always tell the people you interview everything you’re thinking. So you keep some things to yourself. And you have an agenda,” Ted Conover told me.

In any investigation, a journalist shares only part of the information they hold with their sources. Rarely do they disclose the full scope or intent of their reporting. This isn’t out of malice, but out of necessity, to avoid losing access, to prevent a source from shutting down or steering the conversation away from the journalist’s true line of inquiry.

Even without resorting to fake names or fabricated backstories, every investigative journalist, in some form, deceives the people they speak to. Not to manipulate, but to pierce through layers of opacity and gain access to truths that would otherwise remain hidden.

But not all deceptions are created equal. If we were to imagine a scale of deception, at the lowest level we’d find omission, the simple act of not revealing the true goal of a story. At the highest end, we’d place full impersonation: the construction of a false identity complete with a backstory. Traditional journalistic ethics draw what appears to be a clear line somewhere in the middle, between omission and outright lying. But look closer, and that line becomes much blurrier than it first seems.

Lying is undoubtedly the most direct, and most controversial, way to deceive a source. For many, it’s ethically unacceptable.

But let’s complicate the picture: what would we think of a journalist who, to confront a priest accused of abusing deaf children, pretends to be a former student and manages to get a confession that prosecutors never could? In cases like this, the moral calculus becomes far less clear, and public interest can come into conflict with the profession’s traditional ethical code.

We won’t attempt to solve that dilemma here. But we do want to ask a more concrete, pressing question: is it possible to do undercover journalism, to uncover difficult truths, without ever lying?

Judging by Ted Conover’s story, the answer just might be yes.

Sing Sing

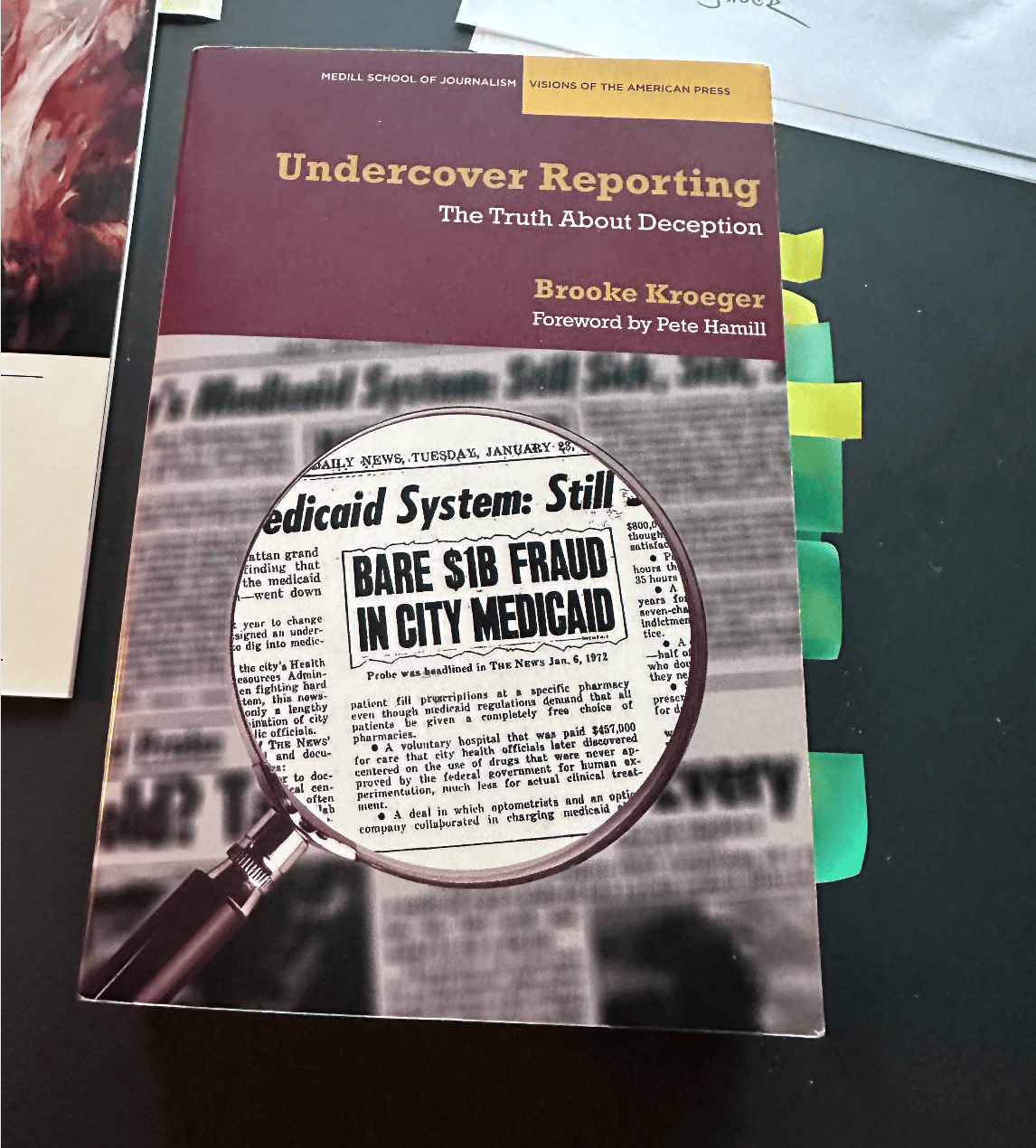

To write Newjack, his most acclaimed book and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Ted Conover spent an entire year undercover as a corrections officer in one of the most notorious prisons in the United States: Sing Sing.

Sing Sing is a maximum-security facility, infamous not only for the harshness of its conditions but also for the criminals it has housed, figures like Lucky Luciano, the legendary mafia boss, and Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, the ruthless leader of Murder Inc., an actual “murder-for-hire” enterprise the Italian-American Mafia used to eliminate its rivals. Authorities confirmed around a hundred homicides tied to the group, though the real number is suspected to exceed a thousand. But that, as they say, is another story.

Conover initially tried to gain access to Sing Sing as a journalist. His request was denied. At that point, he was left with two options: get arrested or get hired. He chose the latter.

Ironically, it wasn’t the easier path. He had to apply for the official civil service exam to become a corrections officer. After passing, he underwent a series of interviews and psychological evaluations, during which he told the truth about his identity and background as a freelance writer, without, however, disclosing the real reason for his application. Once accepted, he enrolled in the New York State Corrections Academy, where he completed a seven-week intensive training program on prison regulations, use of force, inmate management, and paramilitary discipline.

Only after completing this process, competing with hundreds of other candidates, did he receive the long-awaited assignment to Sing Sing, where he began working full-time.

As one might expect, the experience was exhausting. Spending a year inside a maximum-security prison, in daily contact with violent inmates, is not for the faint of heart. Conover endured grueling shifts, chronic stress, and, above all, profound emotional isolation.

“I had to keep a secret from my friends and my neighbors and my family for almost a year, and it was very isolating, emotionally very challenging,” he told me.

Very few people knew about the project. Like many undercover journalists, Conover lived two parallel existences: on one side, the “newjack” (slang for rookie officer), responsible for maintaining order behind bars; on the other, the journalist, silently observing and taking notes on the daily dynamics between guards and inmates, many of whom were young Black men caught in the machinery of mass incarceration.

His aim wasn’t to create a sensational exposé. It was to understand, deeply and from within, a closed, opaque system that affects millions of Americans but is seen by almost none. And to do that, he had to live it. Become part of it.

This approach has a name, one that suits it beautifully: immersion reporting.

Underwater

Undercover journalism is generally used as an investigative tool to access hidden or restricted information. It’s a method not unlike hacking: the journalist breaks into a closed system in order to extract data. Think of a reporter pretending to be a former student to get a confession from a priest accused of abuse. In those cases, the objective is clear-cut: to prove whether something did or did not happen.

Ted Conover’s approach, however, is different. His infiltrations are not about exposing a secret, but about understanding a world, living in it, observing it closely, and experiencing it from within. It’s no coincidence that his work falls under the category of immersive journalism, a genre that doesn’t settle for reporting from the outside but instead plunges directly into reality, remaining embedded for weeks, months, or even years.

“Before you even get to what you learned, the fact that you were in that room is interesting and dramatic,” he told me.

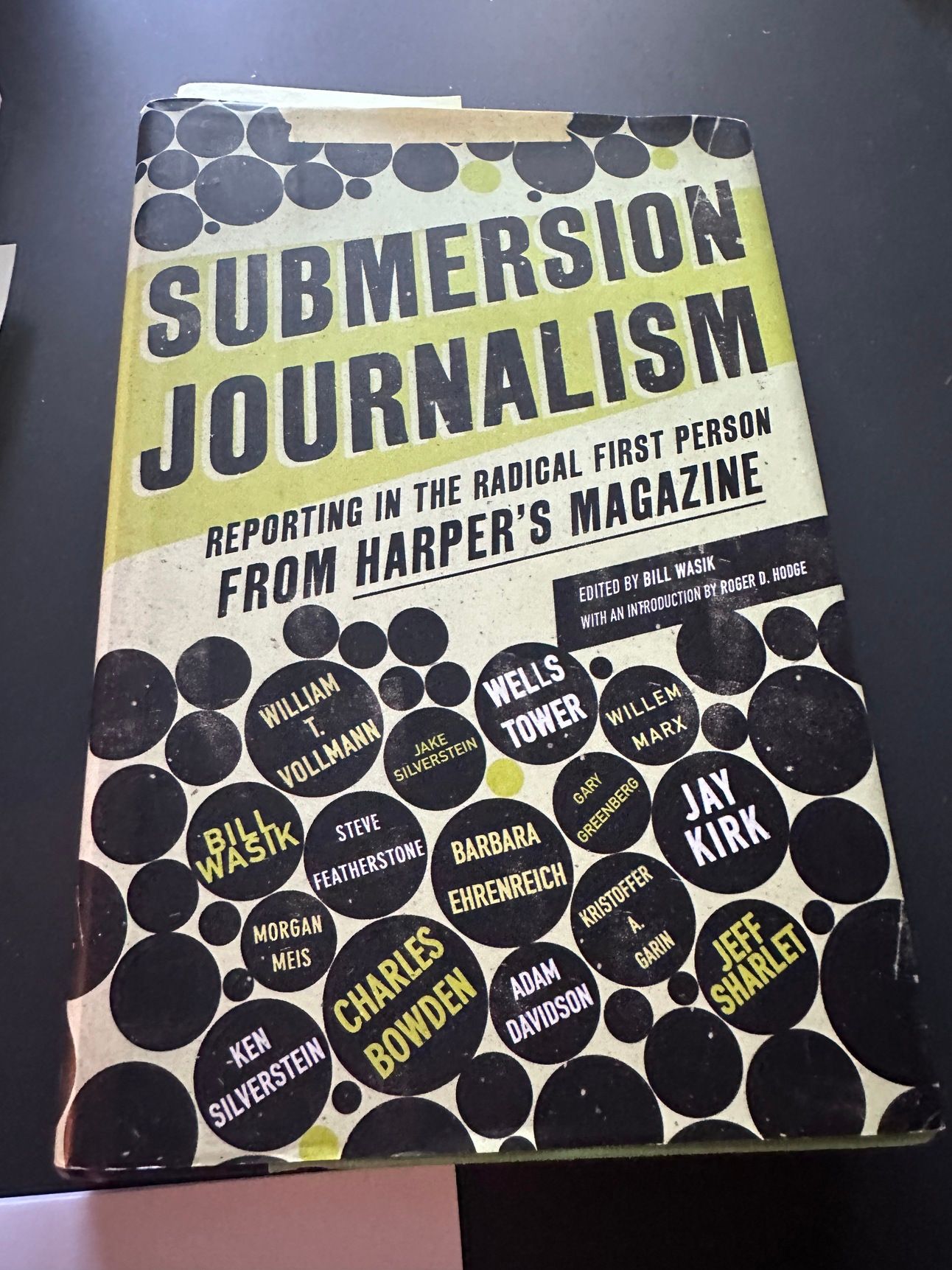

Conover’s method is deeply influenced by his training in anthropology. His writing adopts ethnographic techniques: participant observation, cultural sensitivity, and the suspension of judgment. But there’s something else that defines his work, empathy. For Conover, storytelling also means forming a human connection with the people he writes about. It’s no surprise he has taught courses like Journalism of Empathy and Undercover Reporting at New York University. The latter, to our knowledge, is the only academic course in the world dedicated entirely to undercover journalism.

And yet, what truly sets his investigations apart is a strict rule he’s always followed: never lie. He has never invented an identity, never fabricated a backstory to gain access. Instead, he lets the system admit him on its own terms, simply withholding certain details rather than falsifying them. It’s an incredibly fine line to walk, one few are able to navigate. But it’s precisely in that balance, in the honesty toward the reader and the deliberate restraint toward the subject, that the ethical strength of his work resides.

Never Lie

When I first met Ted Conover last year, I was in the middle of a kind of journalistic identity crisis. I had just come out of a heated debate with my investigative journalism professors, ones of the most respected investigative reporters in America (I won’t name them here) – who are firmly against any form of deception. To them, lying to obtain information meant betraying the profession itself.

I still remember something Ted told me during our conversation in New York. I’m paraphrasing, but the essence was this:

“A journalist should never lie to their audience. That’s the trust that must never be broken.”

It struck me as a powerful distinction. Because it separates two different levels of trust: one between the journalist and the reader – a sacred bond built on honesty and transparency – and one between the journalist and their sources or subjects. In this view, the journalist is accountable first and foremost to the reader, not to the people they investigate. To the former, they owe truth and clarity. To the latter, they may omit, but must never distort.

This perspective becomes even more meaningful when you realize that Conover has never lied, not even in his most extreme undercover projects. When he applied to work as a corrections officer, he used his real name, declared his background as a writer, and listed genuine work experience. He didn’t invent a persona or forge credentials. He simply left out certain information, such as the fact that he was planning to write a book. His resume included years of freelance and side jobs, which didn’t raise any red flags.

And when, during an interview, a psychologist asked him why he wanted the job, he replied:

“People change.”

Ted Conover in his studio at New York University in Lower Manhattan wearing a helmet used during an undercover investigation.

It wasn’t a lie. It was an ambiguous truth, left floating in the air. His silence wasn’t fraud, it was a calculated, conscious omission, a gray zone he navigated with care, always asking himself whether it was ethically justifiable and legally sound. It’s a fragile balance, one that many might find impossible to maintain. But it’s exactly on that thin line, between what is left unsaid and what must be revealed, that the moral core of Conover’s immersive journalism resides.

And if you’d like to hear it in his own words, and haven’t yet clicked, here’s the recording of our conversation:

For everything else, see you in the next Debrief,

Luigi & Sacha

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at:

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply