- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- The Journalist Who Bought a Child to Expose a State Crime

The Journalist Who Bought a Child to Expose a State Crime

In 1885, an investigation shook Great Britain to its core: it led to the passing of a law that saved thousands of lives, shocked public opinion, and landed its author in prison.

We have often asked ourselves whether an investigation can justify a conviction. Whether lying, deceiving, or even breaking the law can be justified when the goal is to expose a corrupt or inhumane system. In 1885, an English journalist named William Thomas Stead staged an operation so extreme that he purchased a 13-year-old girl to demonstrate how easy and widespread this practice was in London at the time.

This is the story of that investigation: The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon, and how it directly influenced the political agenda of Victorian England.

This issue was written by Luigi and edited by Sacha.

Speaking of investigations that shift the political agenda:

On Tuesday, May 13th, I will be in Milan with Jean Peters from Correctiv, author of Secret Plan Against Germany, an undercover investigation revealing a secret meeting between AfD, Germany's far-right party, neo-Nazis, business leaders, and members of the CDU, Germany’s conservative party. They gathered to discuss a mass deportation plan for non-European immigrants—a concept known as "remigration." This investigation anticipated the propaganda of Europe's far-right movements, and Peters also transformed it into a theatrical performance titled Schwarz Rot Braun – Black Red Brown.

In this Issue of Debrief:

Five pounds for Eliza

London, July 1885. A woman lets strangers into her home and accepts their offer: five pounds in exchange for her daughter, Eliza Armstrong, aged just thirteen. They tell her that the girl will go to work as a servant for a respectable family. The mother accepts without asking too many questions. Eliza is picked up the same day by a well-dressed woman, taken away in a carriage, then to a beautiful house in the center. This was common practice throughout London. Everyone knew what happened to these girls: they were drugged, locked in basements to stifle their screams, raped, and forced into prostitution. For the rest of their lives.

Eliza, however, never ended up in a brothel. She was taken away by feminist activist Josephine Butler and her freedom was bought by journalist William Thomas Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, who was determined to show how easy, legal, and common it was to buy a child in London and force her into prostitution. When he realized that Parliament was allowing a bill to raise the age of consent from 13 to 16 to languish, he decided to force the issue. The only way to shake people's consciences was to show them the horror. The staging was enough to prove everything: the complicity of families, the efficiency and widespread nature of the trafficking, and the inertia of the law.

When Eliza woke up, she was in a safe house. She had not been touched or sold. But her story, published a few days later, shook Westminster. It was living, disarming proof that London—Victorian, imperial London—lived undisturbed despite the silent tribute of its most fragile and defenseless creatures.

Theseus, the Labyrinth, and the Tribute to the Minotaur

On July 6, 1885, the Pall Mall Gazette published an explosive headline: “The Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon.” William T. Stead released a four-part investigation over five days that read like a horror novel: boys and girls sold for a few shillings, complicit doctors, desperate mothers.

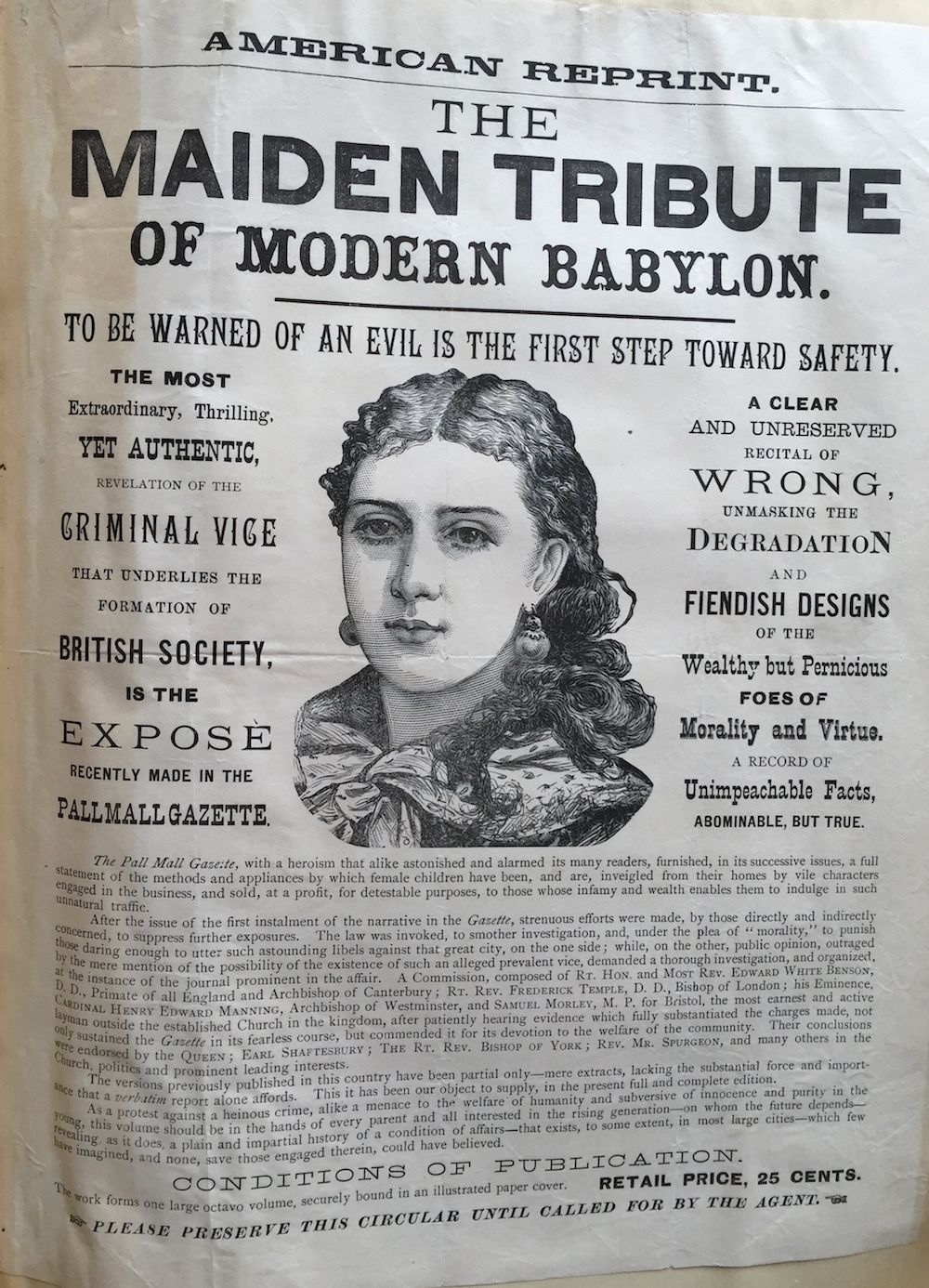

An American reprint of Stead's investigation

London was depicted as a modern Babylon, corrupt and dominated by a metaphorical Minotaur: men's appetite for virginity. Just as in the myth, the monster could only be appeased through a regular tribute of young and innocent lives.

To defeat the Minotaur, Stead drew upon this myth, casting himself as Theseus, the legendary hero who slayed the beast. The journalist had to infiltrate the labyrinth, locate and kill the monster with a poisoned sword, thus ending the sacrifice of innocent human lives.

“For four weeks, aided by two or three coadjutors of whose devotion and self-sacrifice, combined with a rare instinct for investigation and a singular personal fearlessness, I cannot speak too highly, I have been exploring the London Inferno. It has been a strange and unexampled experience. For a month I have oscillated between the noblest and the meanest of mankind, the saviours and the destroyers of their race, spending hours alternately in brothels and hospitals, in the streets and in refuges, in the company of procuresses and of bishops.”

The style of the articles was theatrical, at times disturbing. The boundary between reporting and fiction was thin and perhaps intentionally blurred. The Maiden Tribute was a sensational publishing success: although the main newsstand chains refused to distribute the newspaper due to its content, armies of street vendors and Salvation Army volunteers took to the streets to sell it. Thousands crowded to obtain a copy; even playwright George Bernard Shaw offered to volunteer as a street vendor to help spread the word.

A reform addressing this issue, as demanded by Stead, was passed within days. Just two days after the first article appeared, the House of Commons urgently resumed debate on the Criminal Law Amendment Bill, which had been stalled for months in parliamentary limbo.

The new law was enacted in just over a month and became known as the “Stead Act.” It marked a turning point in child protection policies. Firstly, it raised the age of consent for girls from 13 to 16 years old, making any sexual act with a person under that age prosecutable as rape. It also significantly increased penalties against child prostitution, exploitation, and sex trafficking. This was a groundbreaking reform. In short, Theseus had reached the Minotaur, dealt a mortal blow, and—just as in the myth—managed to escape from the labyrinth, rescuing hundreds of thousands of innocent lives in the process.

A Journalist, A Criminal

Stead’s investigative series threw respectable Victorian society into panic, forcing institutions to react. But, as often happens in stories like these, the journalist who exposed the crime also paid the price. Rival newspapers began digging into the affair and soon discovered that the man who denounced the crime had, in fact, also committed it.

Indeed, Stead had written his investigation without ever explicitly stating that he himself had bought Eliza Armstrong. Throughout his reporting, he kept the detached perspective of a chronicler. When confronted with the accusations, however, he did not deny anything. He admitted that he had broken the law in order to change it. He was charged and sentenced to three months in prison for kidnapping.

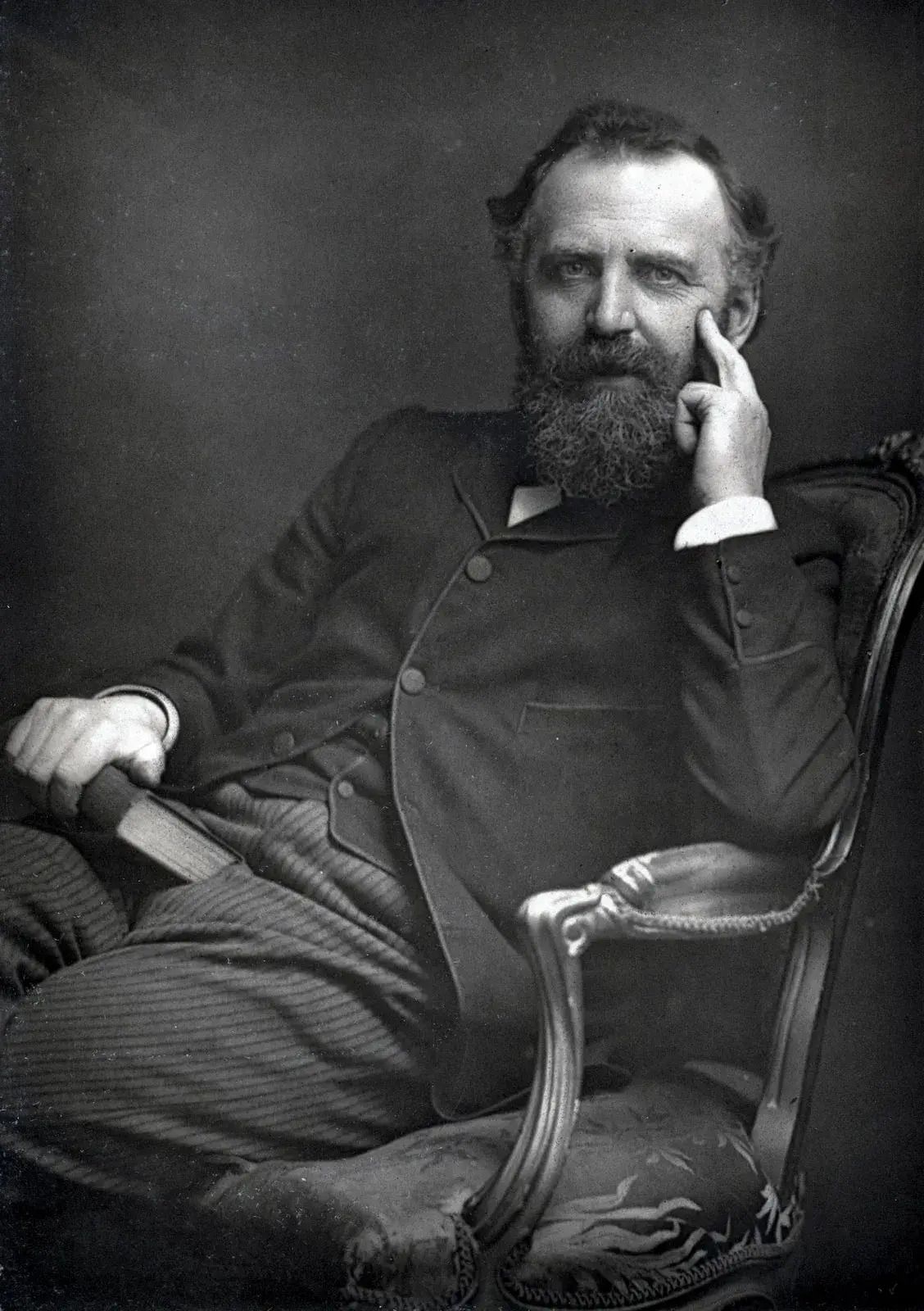

A portrait of William Thomas Stead.

Meanwhile, Eliza was placed in a secure boarding school. She grew up away from the spotlight, receiving an education and a second chance. As an adult, she moved to the northeast of England, married, and had ten children. She continued writing to Stead until 1906, but never made any public statements—neither to condemn nor to justify him. Many regarded Stead as a hero, others called him a hypocrite. They wrote that he had used child trafficking to fight child trafficking. He introduced a new form of journalism, with which few had experience. But he also left an open question: how far can a journalist go to expose injustice?

Forgive me for continuing with the metaphor of Theseus, but Stead himself evoked it, and he would probably be pleased to know that his life continues to be read through this allegory. Theseus, like many Greek heroes, also carried within him a tragedy. Returning home, he forgot to change the sails on his ship—the prearranged sign agreed upon in the event of his success. Seeing the unchanged sails, his father believed him dead and threw himself into the sea out of despair. And, much like Theseus’s victory, Stead’s triumph was accompanied by an unintended tragedy.

Because, at the last moment, into the very same law that banned child prostitution was inserted an unrelated provision—the Labouchère Amendment—which criminalized male homosexuality. This amendment opened a long season of legal persecution in Britain, lasting until 1967.

The Sinking Ship

The Maiden Tribute not only transformed British law—it also reshaped journalism. In 2012, journalist Roy Greenslade, writing in The Guardian, described Stead as "the founding father of investigative journalism," as well as "the inventor of the sensationalism that gave rise to the tabloid newspapers" of the twentieth century. In a sense, Stead, two years before Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-House, employed a type of journalism we could undoubtedly label as undercover—though not in the traditional sense. His journalism was investigative reporting conceived as a performative act: journalism that staged truth and forced it without ever revealing deception until compelled to disclose it by a court order. This is the fundamental difference between Stead’s investigation and Bly’s, which remains history’s first complete and self-aware example of undercover journalism.

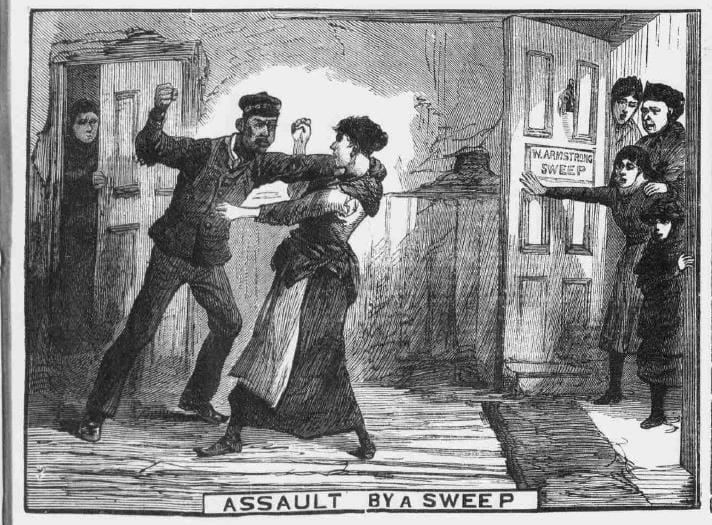

An illustration from one of Stead's stories.

Yet Stead’s life held other surprises. In 1912, Stead boarded the Titanic on its maiden voyage—the lexical coincidence with The Maiden Tribute is eerie. He died on the night of April 15 when the ship sank into the Atlantic. According to eyewitnesses, he helped women and children on lifeboats and gave his life jacket to another passenger. His body was never recovered.

It has often been noted that, years earlier, Stead had written stories foreshadowing a similar tragedy: a large, overly confident ship, equipped with too few lifeboats, crashing into an iceberg or another vessel. Calling these writings "self-prophecies" might be excessive, but the symbolic resonance behind this entire story remains difficult to ignore.

Narrating Evil, Crossing Through It

We tell this story today because it speaks to us about boundaries. Boundaries between good and evil. Between fiction and truth. Between ethics and success. Stead raised a question that remains open today, every time a journalist puts on a concealed camera, every time power is deceived for the public good.

Who decides where the duty to inform should stop? At a time when journalism has become domesticated, The Maiden Tribute remains a stark example of what it truly means to be radical.

Until the next Debrief,

Sacha and Luigi

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at::

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

We've also launched a podcast featuring interviews with the authors of memorable undercover investigations:

👉 https://open.spotify.com/show

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply