- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- When Undercover is an Art Form

When Undercover is an Art Form

German journalist Jean Peters shows us how much performance there is in going undercover.

In this newsletter we often talk about undercover journalism as an investigative technique or as a method used by law enforcement. But we have never looked at an undercover operation as an artistic performance. Yet to investigate in this way, you have to introduce a small element of fiction into reality, and that fiction—both in its conception and its execution—is a truly performative act.

To help us reflect on this delicate balance between real and fictional, we met with Jean Peters, a German investigative journalist at Correctiv, one of the most interesting investigative journalism organizations in Europe. Peters is the author of numerous investigations that have made the rounds worldwide, including Secret Plan Against Germany, in which he exposed an alliance of European right-wingers around a “remigration” plan—a project for the mass deportation of migrants.

Before applying the undercover method to investigative journalism, however, Peters first used it within the art collective Peng!, which he co-founded.

I met him in Milan, where he had come to discuss the undercover method with me in front of an audience of students and journalists. He had just set down his suitcase when I hit record. That conversation—now also available as a podcast—was also a way to get to know him better: you can listen to it in full here.

This issue is written by Luigi and edited by Sacha.

In This Issue of Debrief:

When the NSA Was Bombarded with Leaflets

In 2015, outside NSA headquarters in Fort Meade and the BND (the German Federal Intelligence Service) in Berlin, advertising posters appeared encouraging secret service agents to quit their jobs for ethical reasons. The campaign was signed by Intelexit, a supposed psychological support program for intelligence agents in crisis of conscience. The logo looked official, the language was calibrated. It had the appearance of a government campaign. But it wasn’t.

It was dreamed up by the artist collective “Peng!”, which created one of the most audacious media art operations ever staged in Europe: a fictitious but incredibly well-orchestrated campaign to convince intelligence agents to leave their posts, playing on their moral doubts and sense of responsibility. In exchange, the campaign offered psychological and legal counseling services to potential defectors.

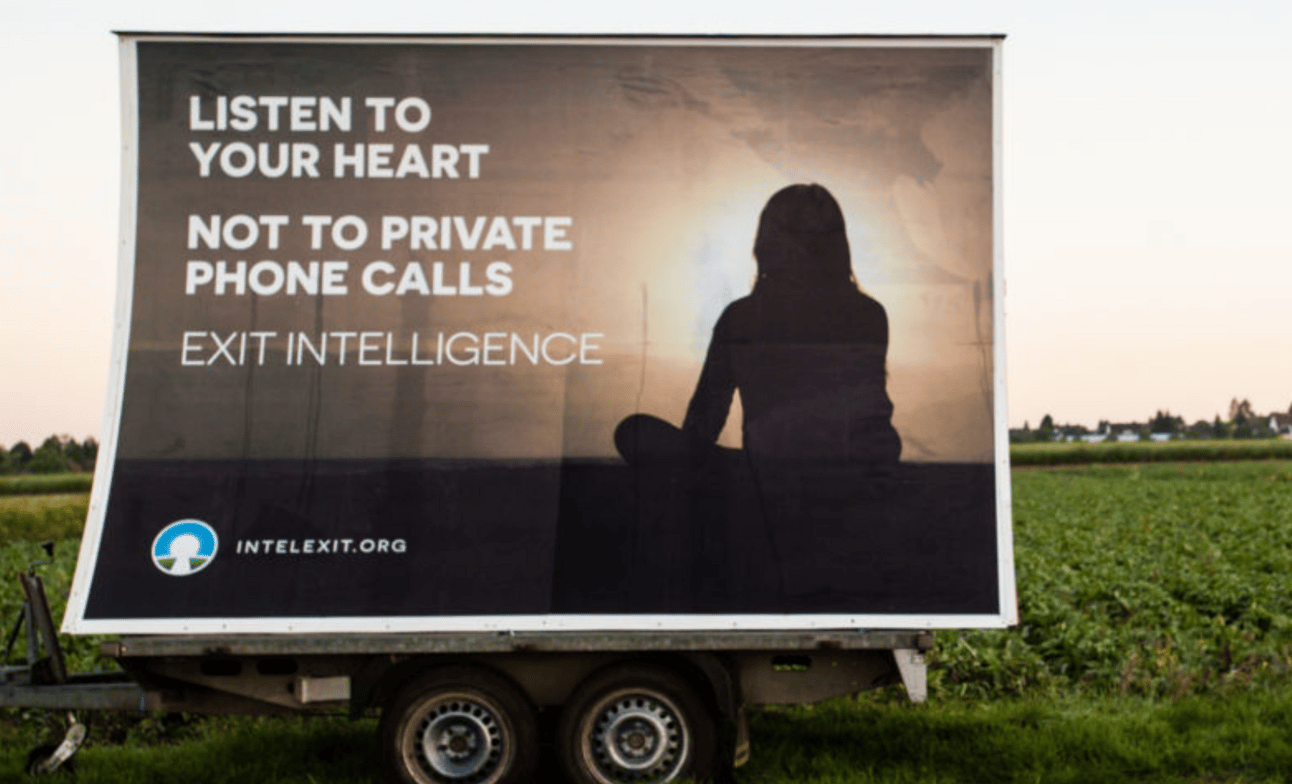

One of the billboards from the Intelexit campaign | Peng!

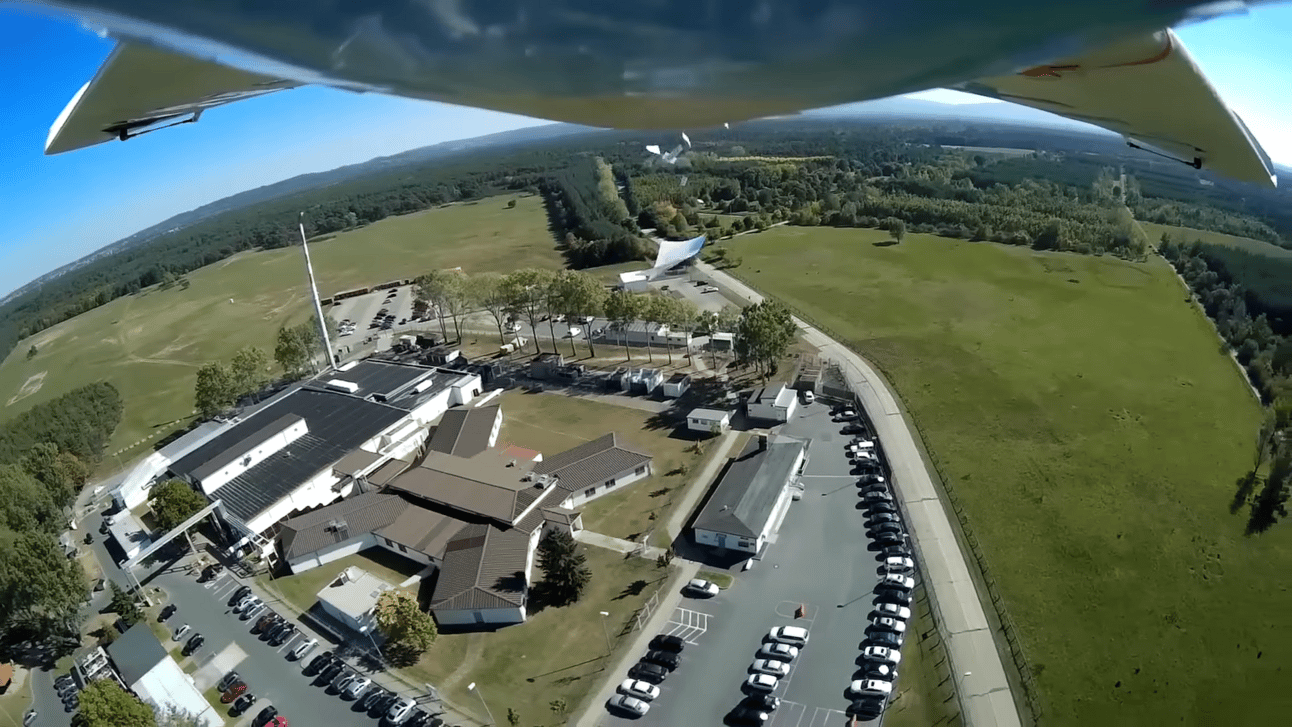

The project operated on several levels: a professional website with an “Exit Now!” section that simulated an aptitude questionnaire, and a social media and print campaign that went viral. Peng! even flew a drone over the NSA base in Griesheim, which dropped hundreds of leaflets inviting agents to join Intelexit — essentially urging them to resign from the intelligence services.

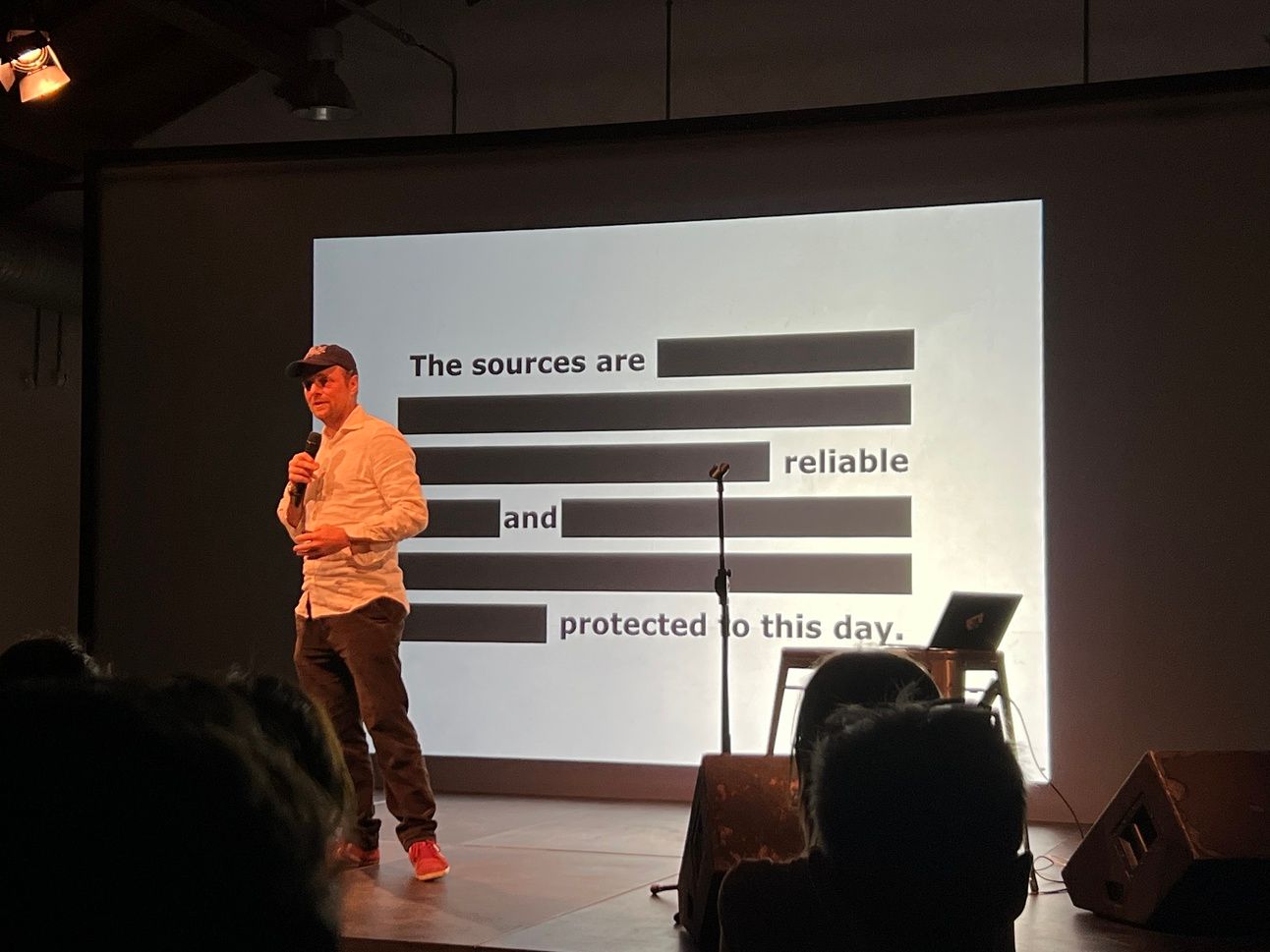

But the real stroke of genius was something else. The leaflets included a phone number for psychological support, and incredibly, secret service agents began to call. But not only that. “We had the phone numbers of 30,000 Secret Service agents in the CIA, the NSA, Germany, France, Canada, and Great Britain,” Peters told me. “And we invited the audience to call them and to talk with them about democracy, because what secret services do, even though they claim to do otherwise, is often to undermine democracy.” People were encouraged to call—not to harass them, but to pose ethical questions. To talk about democracy. To ask: what are you doing, and why?

Peng!’s drone bombs the NSA headquarters with leaflets | Peng!

For three days, there was no reaction. Then something gave. “After the third day, the secret services understood,” Peters recounts. “They read in the newspapers that we were doing this. And when we called, they started to perform. So the performance flipped. All of a sudden, the Secret Service personnel were getting the calls, and they checked their emails for the script they were supposed to read out. They began reading, saying: ‘We’re a democratic institution based solely on the foundations of the Constitution,’ etc. And all of a sudden, the director — who was the press officer of the Secret Service — and the Secret Service spies were performing like actors, pretending to be a democratic institution, and our performers were no longer the audience; the other performers had become the audience.”

Intelexit had another layer: it wasn’t just meant to make the agents reflect, but the public as well. The idea was to expose the inherent opacity of the secret services by staging them. Not to ridicule them, but to restore a human dimension to the people within. It wasn’t merely a campaign run by activists who cared about the principles that sustain democracy. It was tactical media art.

What Is Tactical Media Art, Really?

Tactical media art is not propaganda. Nor is it a prank. In its most powerful form, it’s a way to tell the truth by creating disruption, inserting friction into the information channels themselves, and using the grammar of media as raw material to be disassembled and reassembled.

The result is a hybrid, disorienting form of communication: it replicates the tone and format of institutional messaging but subverts its meaning, revealing contradictions that would otherwise remain invisible. Take Zero Trollerance, which was launched in 2015 as a satirical activist operation against online sexism. It consisted of a fake “re-education” program for sexist trolls, presented through a dedicated website and a series of Twitter bots. These bots automatically identified offensive tweets toward women and replied by inviting the trolls to enroll in a self-help program to become feminists. The campaign had a deliberately tongue-in-cheek tone—for example, featuring motivational videos from a fictitious “guru” —but it aimed to expose the problem of misogyny on the internet.

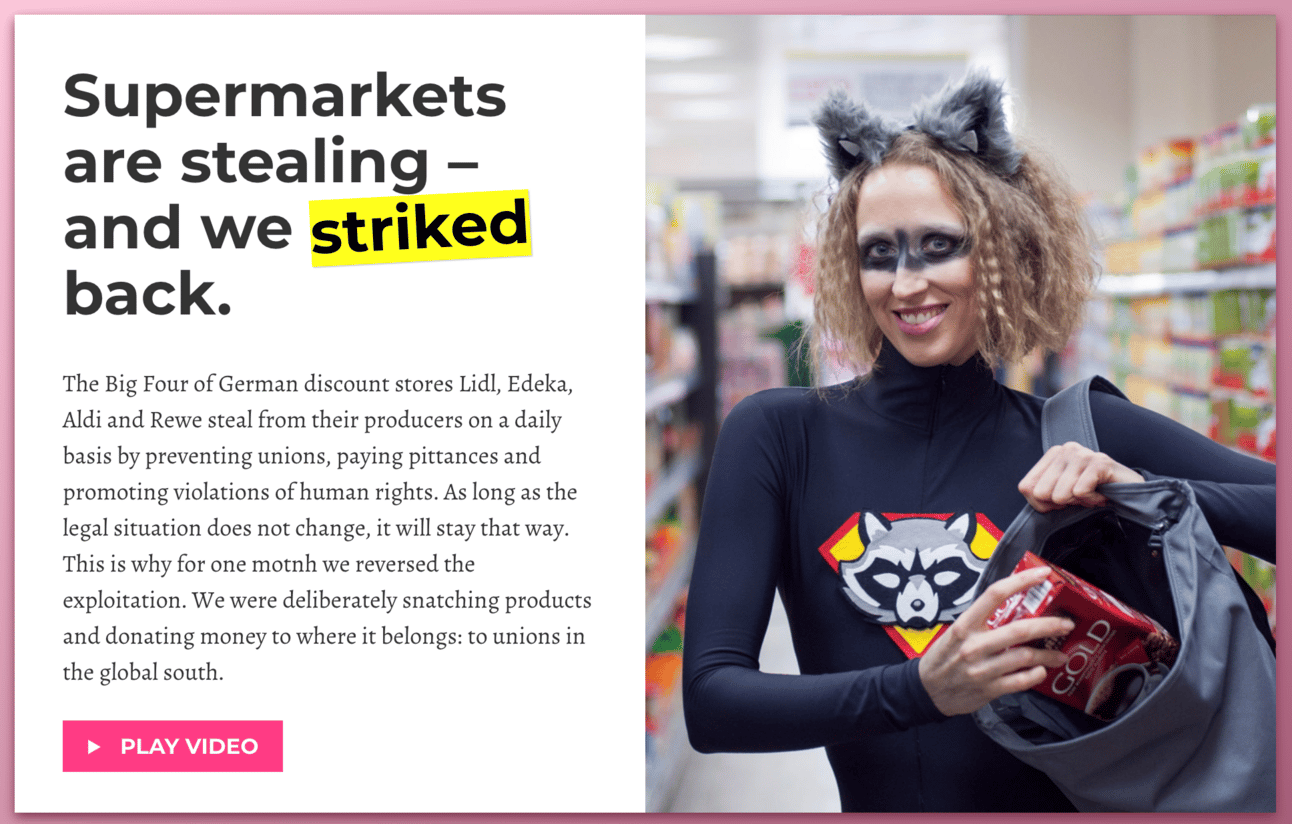

Peng!’s 2018 campaign “Deutschland Geht Klauen” (“Germany Goes Shoplifting”) simulated a fake startup that provocatively encouraged stealing from German supermarkets to symbolically compensate for the colonial exploitation suffered by countries of the Global South. The logic was that major Western retail chains “steal” human rights by paying poverty wages in producer countries, so Peng! flipped the perspective by exhorting consumers to “steal back” and compensate the victims of exploitation. The fact that such a paradoxical idea was delivered in such serious tones was meant to prompt reflection on Germany’s colonial past and its enduring legacy.

One of the promotional videos from “Deutschland Geht Klauen” | Peng!

“There are certain truths you cannot communicate directly from sender to receiver, but you can ensure they get across because they’re very complex,” Jean Peters tells me. “Through algorithms and Big Tech, you can see, for example, how certain information is being pushed up and others pushed down by the gatekeeping of the tech companies. Gatekeepers used to be the TV shows and newspapers; that has changed. We have to rethink the way we create news in ways we currently don’t. Of course, we don’t lie, we don’t fake anything. We’re very transparent. It’s also about reaching those who don’t have time to fully understand—while at the same time providing a new way for information to be received.”

Dismantling power, one identity at a time

Jean Peters has been many things — at least as many as the pseudonyms he’s used. He has been an artist, co-founder of Peng!, an investigative journalist at Correctiv. But his approach has remained the same: to expose the mechanisms of power through a performative act.

“I think there is no possibility not to perform in one way or another,” he told me. “If you look at how society is structured, you can feel it directly. If someone is in a hierarchy, whatever social class he or she is in, that is performance. These are codes. The way you eat, the way you speak, the way you take up space — this is all part of the performance we are in.”

For Peters, infiltration is not just an investigative method. It’s an act of interpreting and staging reality, one that unmasks social mechanisms where they hide best: “Now I’m working as an investigative journalist. Artists and journalists take information and filter it and reassemble it in a way that makes sense. So the way we do it is very different. But the act itself is very similar.”

He proved this when he crossed the boundary between those two worlds, publishing with Correctiv an investigation that shook the German far right and destabilized the national media landscape: “I was a newcomer to the journalism world,” he recalls. “And we did this investigation that was read everywhere. And then the big newspapers felt threatened. They said things like, ‘this is not a journalist like we are.’ So there’s a threat to the integrity of the established media side, and in my case a neo-Nazi threat. They will say, ‘this is not proper journalism, that’s not how you should do it,’ etc., and others will say, ‘this is not true.’ But the truth will always fall on their feet.”

The Secret Plan Against Germany

In January 2024, Correctiv revealed one of the gravest conspiracies in recent German history. It was uncovered by Jean Peters himself, who infiltrated a secret far-right meeting in Potsdam. There, politicians from Alternative für Deutschland, members of the Identitarian movement, businessmen and conservative intellectuals were discussing a “remigration plan” that would change the face of the country forever: deporting millions of people with migrant backgrounds, even if they had been German citizens for generations.

What Correctiv documented was not just an ideological aberration, but a systematic strategy. The architects intended to proceed gradually: first, “censuses” and ethnic registries; then revoking German citizenship from dual nationals not considered of German blood; and finally, mass expulsions. All of this with the silent complicity of economic elites and emerging political actors.

When the investigation came out, Germany woke up with a lump in its throat. The revelation unleashed a collective reaction: over 1.5 million people took to the streets in the following weeks, in one of the largest spontaneous mobilizations since the postwar period. Talk shows caught fire, the Bundestag had to respond, the AfD tried to deny and downplay — without success. The word “remigration” became the symbol of a new authoritarian threat, real and internal.

This investigation showed the German public in an extremely powerful way that it’s not enough to simply document facts; one has to get inside the hidden mechanisms of power to make them visible. And it proved that when an issue is this significant — and perhaps treated superficially by mainstream media — undercover work can manage to shake an entire country.

Let Undercover Change You

Peters is a journalist. But not only that. He stages the truth. He turns investigation into performance. And by doing so, he invites us to rethink what journalism can be when traditional tools are no longer enough.

“If you want to be a good journalist, you have to be curious and get to know the world,” he told me. “Writing well isn’t the most important part. You need to understand the world, to have transcended it, lived with it. You’ve had good food, horrible food, experienced hardship and beauty. Without access to all that, it’s hard to truly understand the world. That’s the basis. From there, we can work.”

And perhaps that is exactly what undercover is. Not just entering an inaccessible system. But letting that system, in some small part, enter you.

Until the next Debrief,

Sacha and Luigi

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at::

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

We've also launched a podcast featuring interviews with the authors of memorable undercover investigations:

👉 https://open.spotify.com/show

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply