- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- Who’s the spy now?

Who’s the spy now?

If any spy can pose as a journalist, then every journalist risks being seen as a spy.

For decades, posing as journalists has been the ideal cover for secret agents. It was their best way to go unnoticed and stay protected. Yet today, the real danger is faced by those who actually are journalists.

The second issue of Debrief explores a paradox familiar to anyone who uses undercover methods: the more you investigate power, the more someone will accuse you of serving it.

Ironically, these accusations often come from journalists who have genuinely collaborated with intelligence services.

Today is Friday, April 25th, a national holiday in Italy celebrating the 80th anniversary of Liberation from Nazi-Fascism. Yet the story we’re about to delve into reveals how certain toxic residues have never completely vanished from our society.

This issue was written by Luigi and edited by Sacha.

In this issue of Debrief:

“Agent Z”: The Journalist Who Spied for the State

Treviso, December 20, 1971. A judge orders the search of a safety deposit box at the bank of Montebelluna, a small town in northern Italy. It's no ordinary box: it belongs to the mother and aunt of Giovanni Ventura, a neo-fascist terrorist suspected of involvement in some of Italy’s bloodiest attacks.

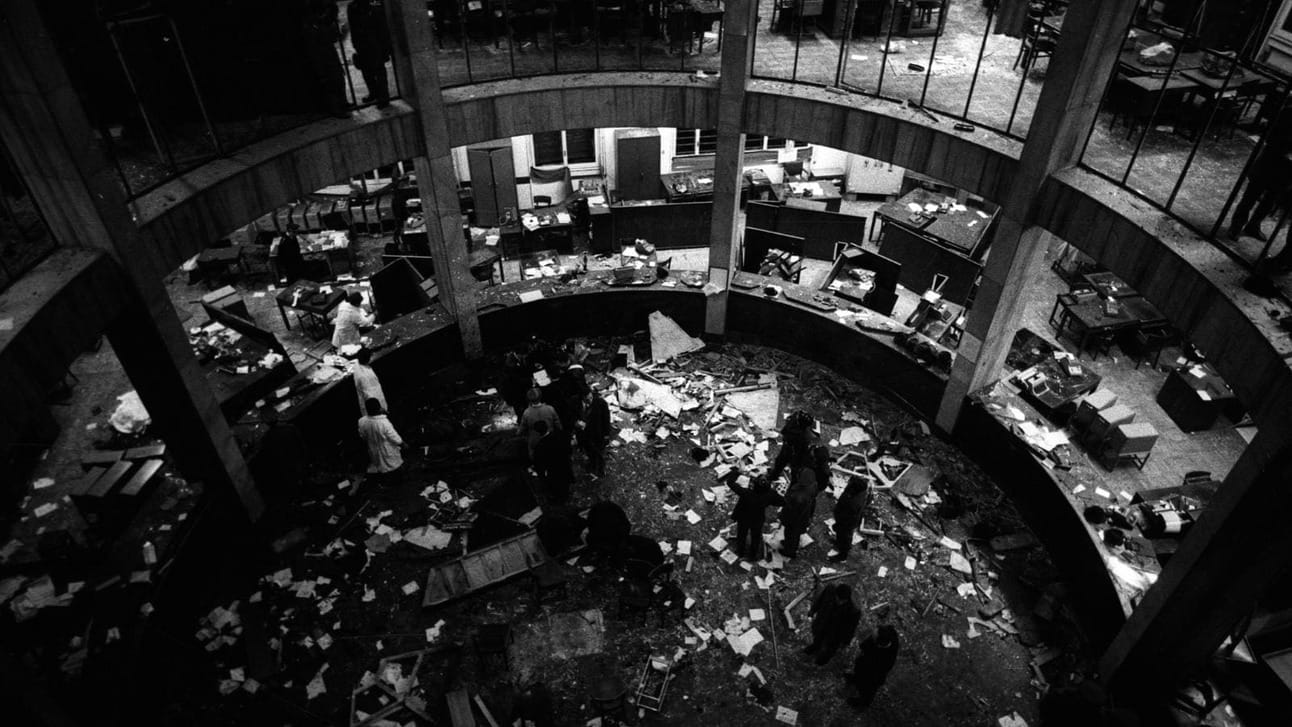

The investigators hope to find evidence linking Ventura to the Piazza Fontana bombing, which occurred in Milan just over two years earlier. On December 12, 1969, an attacker killed 17 people and injured 88 others by detonating a briefcase full of explosives inside the lobby of a commercial bank. It was Italy’s first terrorist attack since World War II, a devastating event that marked the beginning of the so-called "strategy of tension," a prelude to the country's turbulent “Years of Lead.”

An image of the devastation caused by the Piazza Fontana bombing. – Rai Press Office

Indeed, inside that box, the magistrates discover something highly unusual: a stack of classified documents containing sensitive information about secret political maneuvers, military plans, and operations aimed at destabilizing the nation. These were documents no terrorist should ever have possessed. The authorities suspect Ventura had obtained them from a high-ranking figure within the secret services. But when questioned, Ventura surprises everyone by naming a journalist: Guido Giannettini.

Giannettini wasn't just any reporter. He had a background as a militant of the far-right, was well-respected as an expert in military affairs, but behind this respectable facade he concealed a far more significant and shadowy role known to very few. Within Italy’s military intelligence circles, Giannettini was known as "Agent Z."

Guido Giannettini (on the left) and far-right terrorist Franco Freda (on the right) during a hearing of the trial for the Piazza Fontana massacre.

More than just a spy, Giannettini was at the center of an intricate web of covers, infiltrations, and disinformation, serving as a point of contact between intelligence agencies, extremist groups, and state apparatuses. He acted as a bridge between the official state and its darkest shadows, between formal legality and covert destabilization, between journalism and espionage. He used his journalistic identity as cover, attending secret meetings with extremists, transmitting strategic information between the government and subversive groups, and vice versa.

While writing articles openly, he secretly worked to protect the interests and secrets of the powers he served, or at least a particular faction within them. In short, he was a spy operating under journalistic cover, a hidden and unsettling figure in the history of the Italian Republic.

Journalists with a License to Spy

Secret agents posing as reporters is a practice with a long history. From the 1930s to the present day, countless intelligence operations have utilized journalism as their perfect cover. Nobody raises suspicion when a journalist asks questions, meets with politicians, takes photos, jots down notes, or enters restricted locations. It’s part of their job. And this is precisely what made journalism the ideal cover for spies over the decades.

In the 1930s, Richard Sorge, a German journalist stationed in Japan, wrote for the Börsen Zeitung and the Tägliche Rundschau, two prominent German newspapers at the time. But behind his journalistic façade, he secretly worked for Soviet intelligence, passing on critical information about the plans of the Axis powers, the military alliance between Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan during World War II.

In the 1950s, another journalist, Kim Philby, officially worked as a correspondent for The Economist while secretly serving Britain’s MI6 intelligence agency. But Philby wasn't content with serving just one government; he simultaneously passed sensitive information to the KGB, the Soviet Union’s spy agency. This double life made him infamous as one of the Cold War’s most notorious double agents.

Philby on a 1990 Soviet commemorative stamp.

Journalists were frequently among the most effective intelligence assets utilized by the CIA, particularly during the 1950s, 60s, and 70s. In 1977, Carl Bernstein, one of the two reporters who exposed the Watergate scandal, wrote that over the previous two decades, more than 400 American journalists had carried out covert tasks for U.S. intelligence agencies.

These collaborations included journalists from influential media outlets such as Time magazine, CBS, and The New York Times. “In the field,” Bernstein explained, “journalists were used to help recruit and handle foreigners as agents; to acquire and evaluate information, and to plant false information with officials of foreign governments. .”

Occasionally, these intriguing tales of espionage inspired films and literature. For example, BBC journalist Frederick Forsyth, who had cooperated with MI6, eventually became an acclaimed novelist himself, authoring bestsellers such as The Day of the Jackal, a thriller about an assassination attempt on French President Charles de Gaulle, and The Odessa File, a gripping novel about a clandestine organization helping former Nazis evade justice after World War II.

More recently, in 2020, China deployed agents posing as journalists to carry out espionage activities in Britain. This ambiguity repeats itself everywhere and in every era, spies posing as reporters and reporters seduced into working as spies.

Today, however, in the upside-down world of post-truth, genuine journalists often find themselves accused of being spies, viewed with suspicion precisely because their profession has been so frequently co-opted by intelligence services.

Deadly Suspicions

But if anyone can pretend to be a journalist, then every journalist risks being treated as a spy. It’s happened repeatedly, often with deadly consequences.

In 1990, Farzad Bazoft, a reporter for the British newspaper The Observer, was executed by Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq after being falsely accused of spying for British intelligence while investigating a mysterious military explosion near Baghdad.

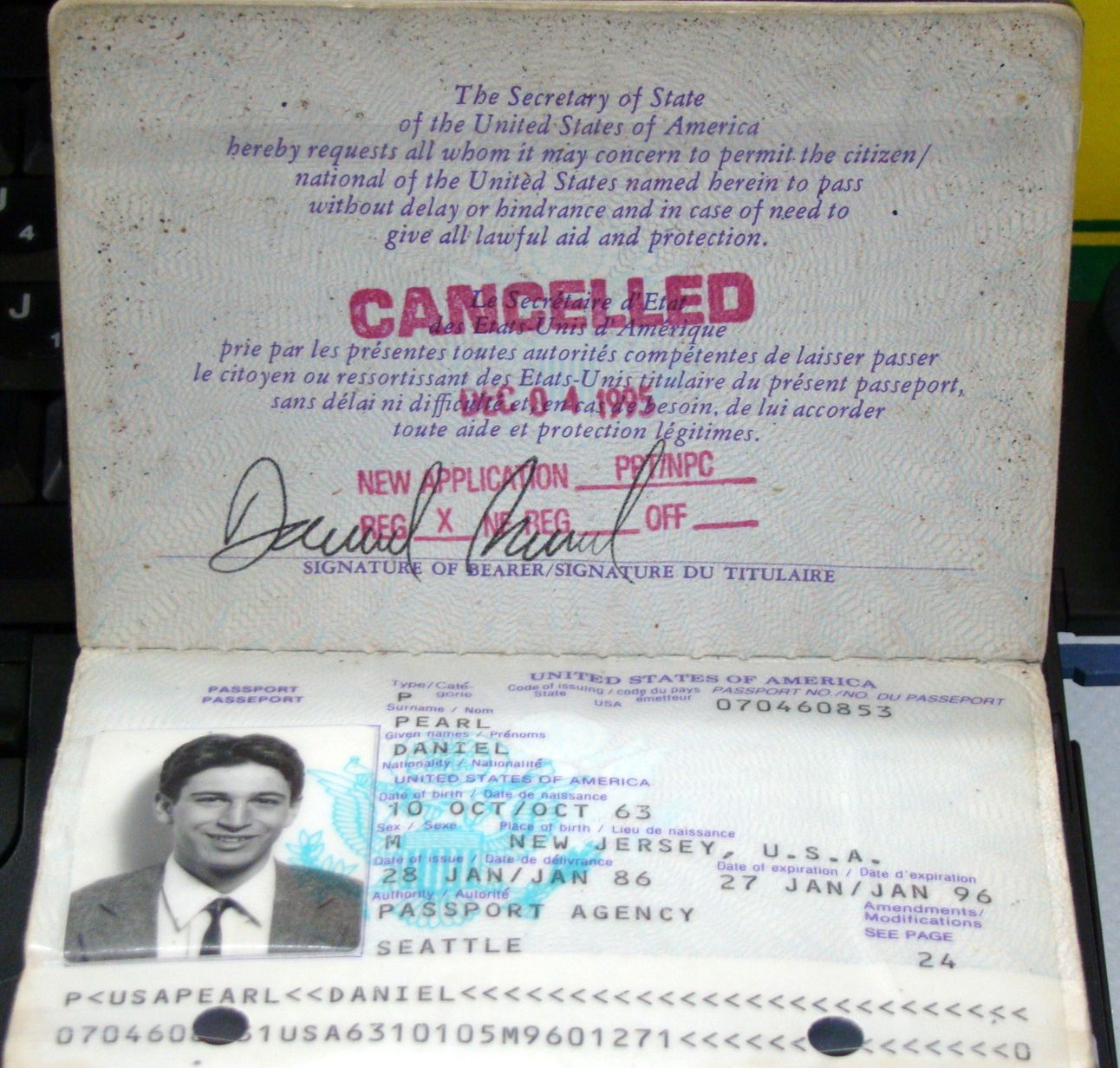

In 2002, Daniel Pearl, a correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, was kidnapped and brutally beheaded in Pakistan by Islamist militants who unjustly accused him of being an undercover agent for the CIA and Mossad, simply because he was investigating connections between local extremists and international terrorist networks.

Daniel Pearl’s passport.

In 2014, Nils Horner, a Swedish journalist working for Sveriges Radio, was shot dead in Kabul by armed men who claimed he was a Western intelligence operative. In reality, Horner was merely reporting on the realities of war-torn Afghanistan.

These were genuine journalists, killed because of a dangerous ambiguity fostered decades earlier by others. Today, in every war zone and under every dictatorship, journalists are viewed with inherent suspicion.

And the blame lies not only with the regimes that persecute the free press: far too many governments, militaries, and security agencies, especially Western ones: have used journalism for their own purposes, spreading false information or exploiting the trust upon which our profession relies.

And so, if spies can freely pose as journalists, who will believe us when we, real reporters, find ourselves in genuine danger?

Who Serves Power, and Who Investigates It?

It's not so complicated, really, but perhaps a quick refresher could help.

Yes, an undercover journalist deceives someone, usually someone powerful, in order to reveal the truth to all of us. They gather information of public interest, verify it thoroughly, and then share it transparently with those who have a right to know: the public.

A spy, on the other hand, collects information on behalf of a government or state. A spy does not answer to citizens, only to their superiors. In fact, they do precisely the opposite of an undercover journalist: they deceive everyone to reveal the truth only to the authorities paying them.

A spy serves power; a journalist investigates it. The spy protects the institutions they work for; the journalist acts in the public interest. Journalists disrupt power, while spies reinforce it. This distinction is crucial and worth repeating.

When They Called Us Spies

In October 2021, after publishing our undercover investigation, "Black Lobby," which exposed connections between far-right groups and institutional politics in Italy, Renato Farina, a journalist at the Italian newspaper Libero, repeatedly accused us:

“This isn't journalism, it's misdirection.”

“They wielded a couple of video clips like a loaded gun.”

“They're scalp hunters serving the Left.”

“It's garbage. They don't report facts; they selectively assemble fragments to create sensationalism. That's the method of agent provocateurs.”

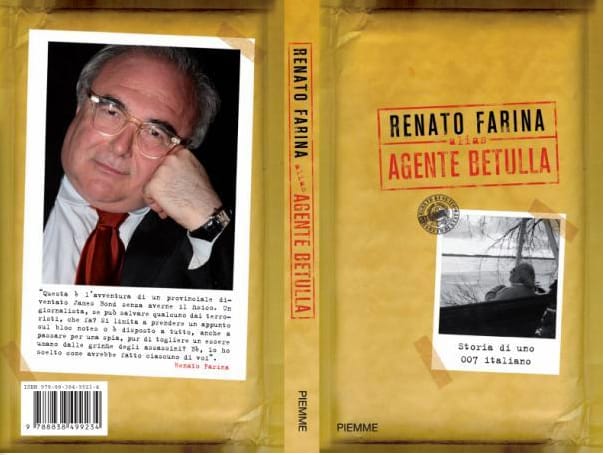

Farina is a journalist and political commentator specializing in domestic politics. But notably, since 1999, he has collaborated with the Italian military intelligence services under the code name "Agent Birch”, (in Italian “Agente Betulla”). He denies acting as a spy, but in his book, Alias Agente Betulla, he admits: “I met and listened to intelligence chiefs. I sought their advice. I shared my analyses of events with them; I even warned them about current and upcoming judicial actions. Really? Yes, and I'm proud of it.”

Renato Farina and his book, Alias Agent Betulla.

Because of this collaboration, Farina was expelled from Italy’s Order of Journalists (the official body overseeing journalism ethics and standards) in 2006, only to be readmitted in 2014. This story explains precisely how undercover journalism is undermined and delegitimized.

That’s all for today. Keep resisting.

Until the next Debrief,

Sacha and Luigi

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at:

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply