- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- Why an undercover investigation will never (again) win the Pulitzer

Why an undercover investigation will never (again) win the Pulitzer

The story of the journalists who bought a bar to catch corrupt inspectors

We couldn't launch Debrief without starting with the Mirage Tavern, the most spectacular undercover investigation ever, and with the real reasons why it was excluded from the Pulitzer Prize, relegating undercover journalism to second-class status in the U.S.

This issue is written by Sacha and edited by Luigi.

In this issue of Debrief:

A Personal Thank You

Today is Friday, April 18th. You'll receive this newsletter every week on this day, because this is when Luigi and I have been calling each other for the past year, exchanging the most absurd stories we've come across on opposite sides of the Atlantic.

Debrief is our way of bringing you into those conversations.

Before we get started, we want to personally thank you for subscribing to this newsletter. We know, one by one, the names of the hundreds of people who've already joined us. We're truly grateful for your support: we sought it out, and we'll do our absolute best to deserve it.

To do investigative journalism, you'd better know how to mix a cocktail

It was May 1977 when a 33-year-old man, toolbox in hand, walked into a rundown bar on Chicago’s North Side. Pretending to be an electrician, he headed straight toward the back, as if he had to fix an electrical panel. In reality, there was nothing to fix. He climbed a small ladder, opened a hidden door, and slipped into a secret room located above the bar’s bathrooms, where he'd previously installed cameras behind a ventilation grate.

His name was Jim Frost, and he was part of a team of journalists who had spent days secretly documenting one of the most astonishing corruption scandals in U.S. history.

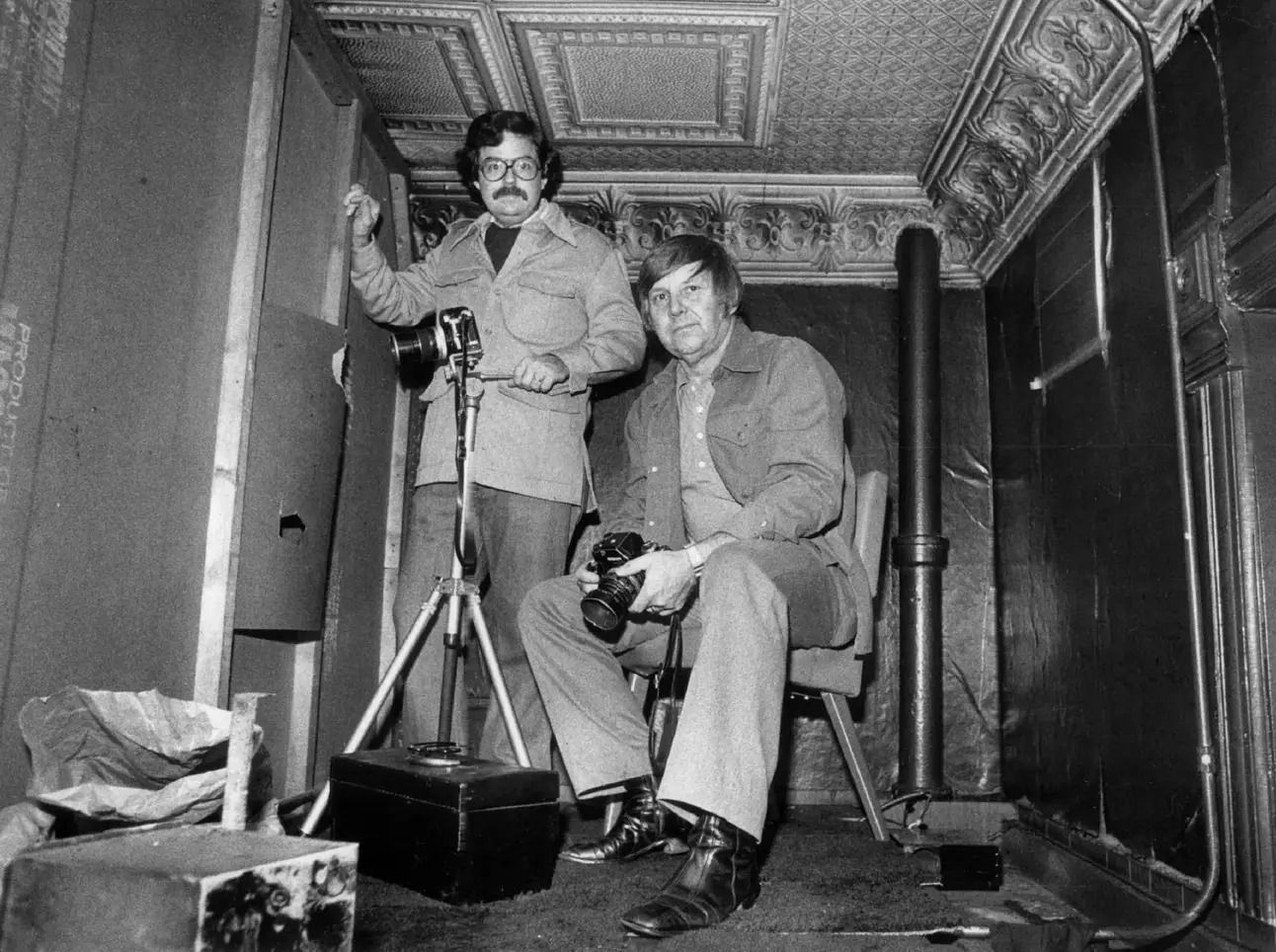

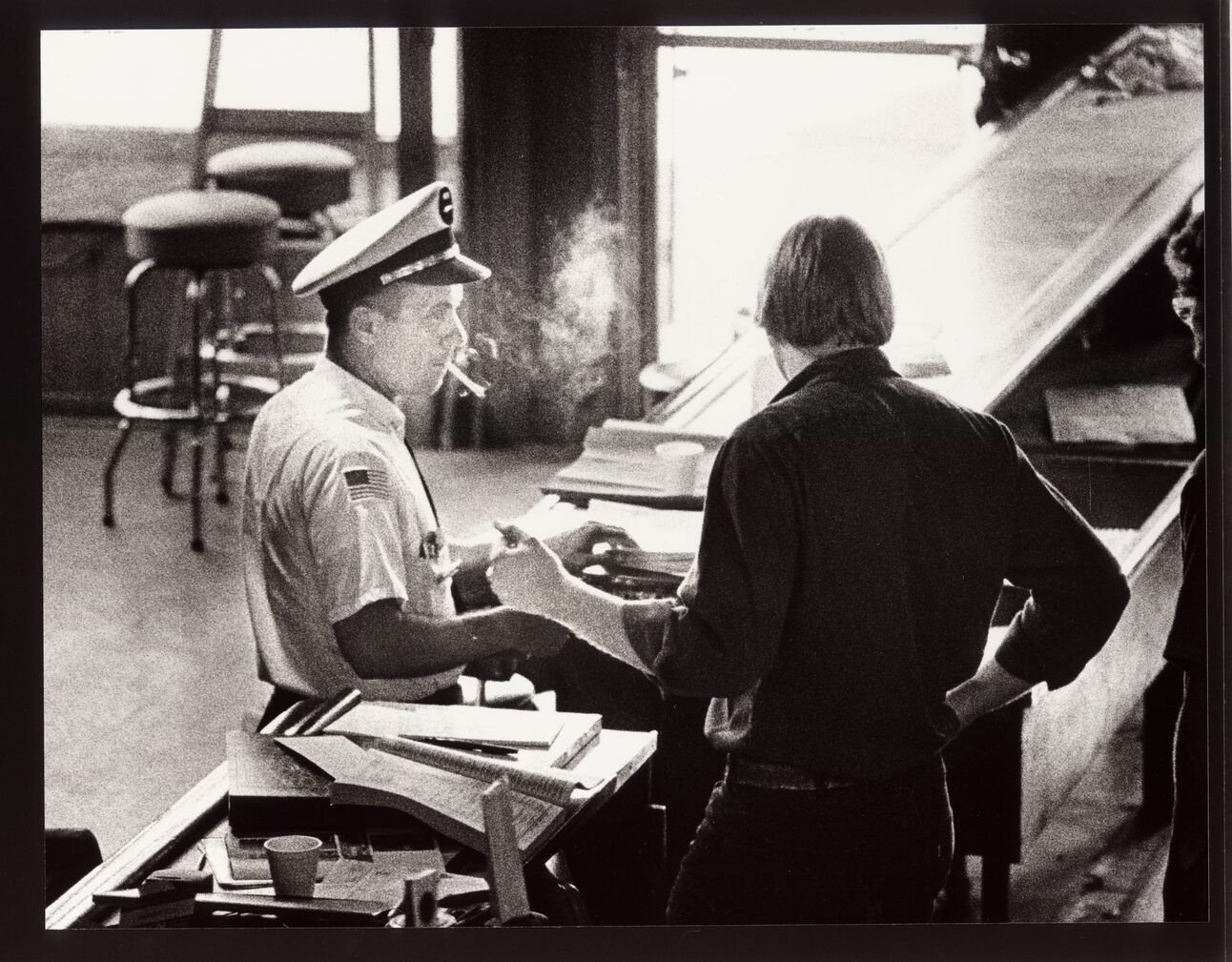

[Jim Frost and Gene Pesek in the Mirage Tavern—or, as we like to imagine it, Luigi and me if we’d been born in black and white] | Sun-Times file

That bar was called the Mirage Tavern and it wasn't just any bar. A few months earlier, it had been bought by the local newspaper, the Chicago Sun-Times, together with an NGO called the Better Government Association, for a specific purpose: documenting the systemic corruption of city inspectors in Chicago, a city then known as a "supermarket of corruption."

It was essentially a trap, a film set designed to lure corrupt officials and expose a widespread system of bribes, complicity, and silence.

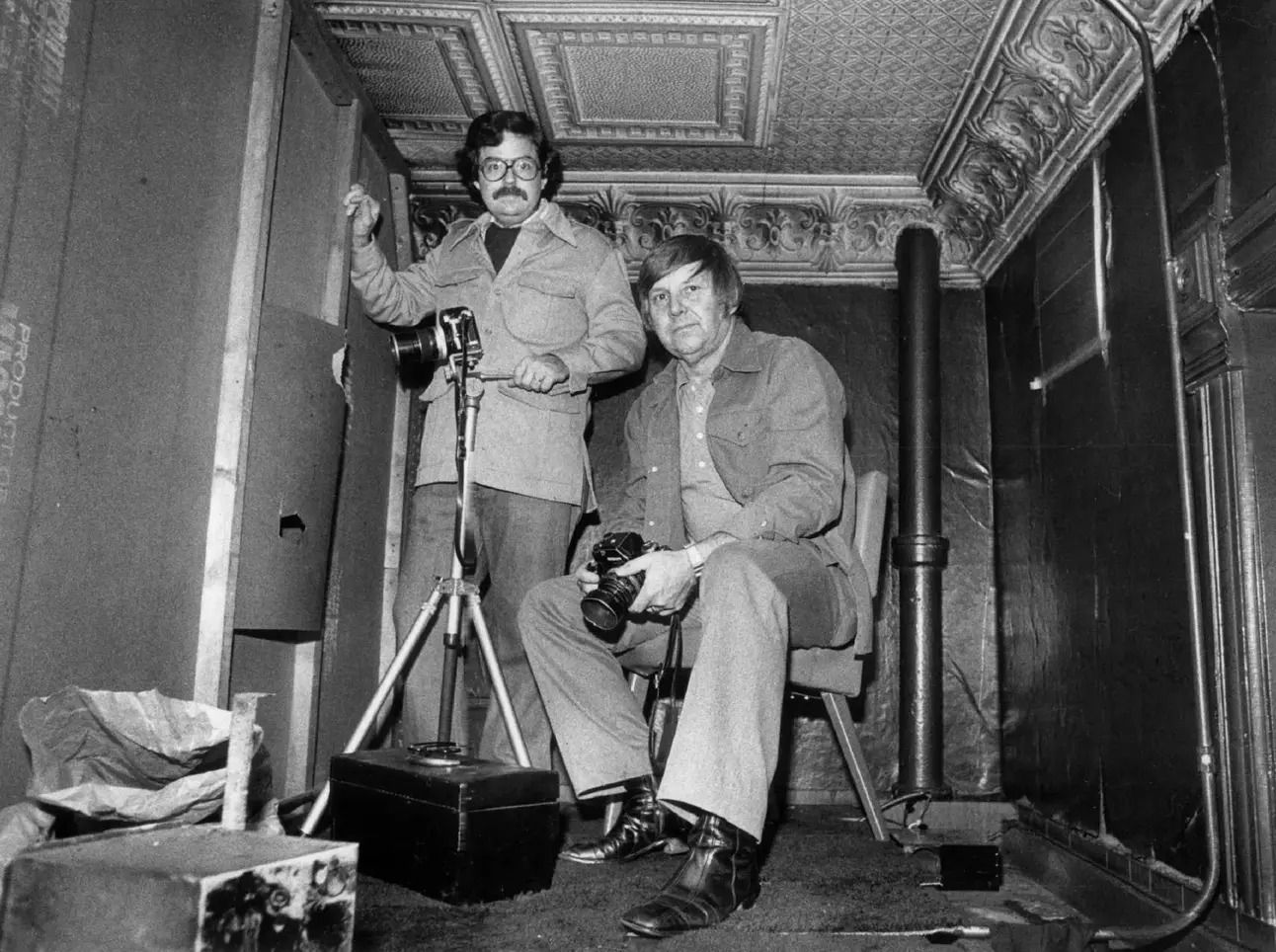

Inside the Mirage Tavern. The secret surveillance spot is visible in the upper-right corner. | Jack Jordan / Sun-Times

The idea was simple: opening a bar would inevitably attract corrupt city officials looking to collect bribes in exchange for issuing permits to stay open. After acquiring the location, the journalists went into action. Young reporter Pam Zekman posed as the determined owner, while her colleague Zay Smith, who had zero experience behind a bar, took on the role of bartender. Meanwhile, from their hidden vantage point above, Jim Frost and Gene Pesek photographed every act of corruption unfolding downstairs.

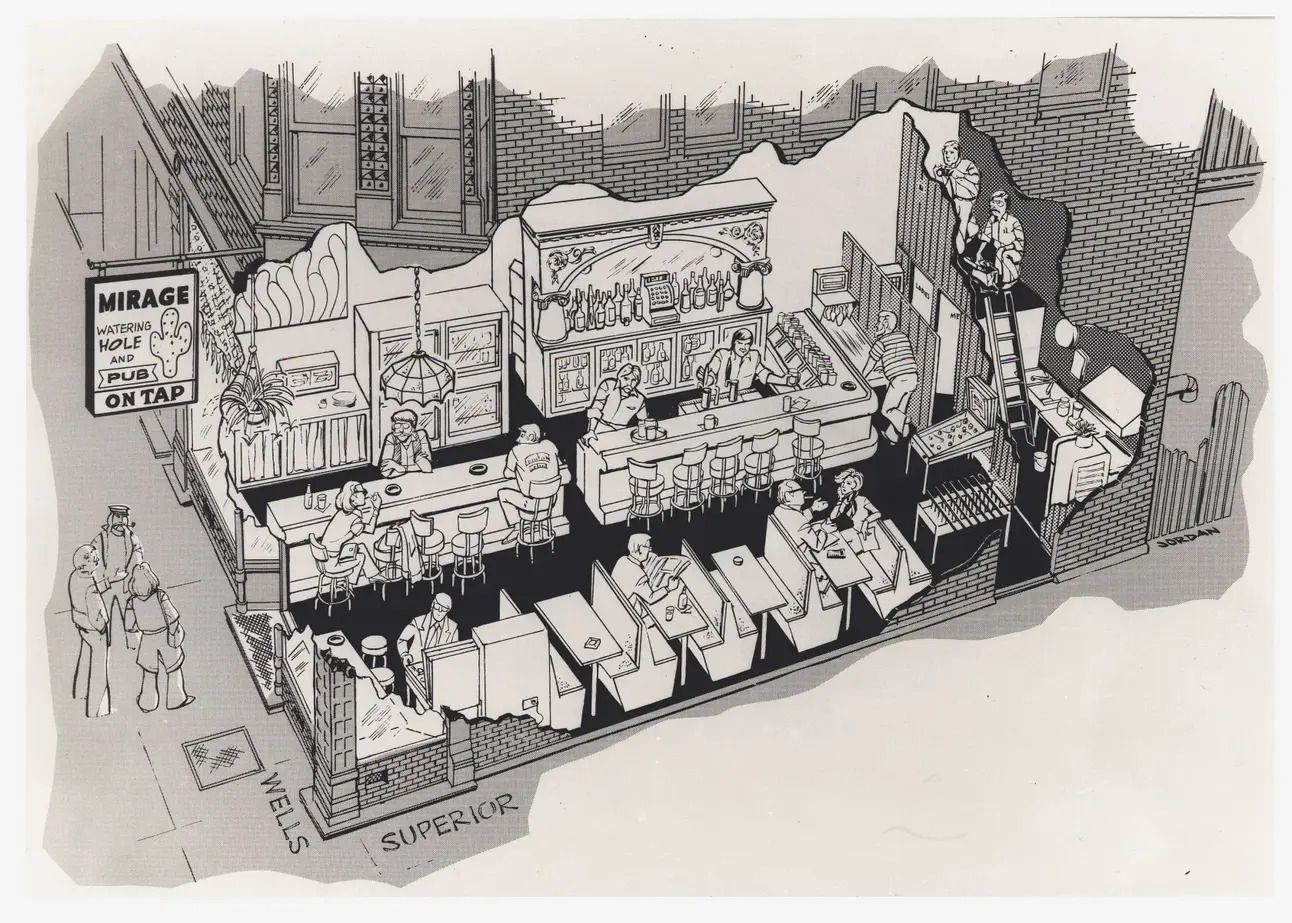

From left to right: Jim Frost, Pam Zekman, Zay Smith, and Gene Pesek in front of the Mirage Tavern. | Sun-Times file

“It wasn’t easy running a bar and conducting a journalistic investigation at the same time,” recalled the legendary Pam Zekman, who described constantly having to deal with furious customers, because Smith, the journalist-turned-bartender, kept messing up the cocktails.

The "Ambush Fishing" Method

The technique they used was the so-called “Ambush fishing”—a fishing method requiring you to remain perfectly still, fully camouflaged within your surroundings, waiting for the prey to spontaneously approach, drawn by an environment it perceives as familiar and safe.

You need to become invisible, blend into your surroundings, and wait. The fish will come to you.

That’s exactly what the Mirage Tavern journalists did: disguised as bartenders and owners, they patiently waited for the city inspectors to approach and ask for bribes. And that's precisely what happened.

Within days, the bar turned into a stage for a constant stream of inspectors demanding money to overlook dangling electrical wires, health officials happy to ignore drains spilling sewage directly into the basement, and even fire department lieutenants signing permits without checking emergency exits. Local accountants even showed up, enthusiastically advising the “owners” on how to systematically evade taxes.

The shot that captures a bribe | Sun-Times file

In just two months of operation, the Mirage Tavern gathered a mountain of photographic and documentary evidence, resulting in an explosive series of 25 articles published beginning in January 1978. The reports included undeniable images of inspectors caught red-handed, bribes still in their grasp.

Eighteen public officials were fired or suspended, shaking local politics to its core and triggering a wave of reforms that reached all the way to the federal level.

“We didn't end corruption in Chicago forever,” Pam Zekman later recalled, “but we’re certain that next time, city inspectors will think twice before accepting a bribe.”

"You do undercover? No Pulitzer for you."

I'm a huge fan of this story, which is why I've been calling Pam Zekman by phone for months (sorry, Pam!). For me, it's like getting to talk directly to Nellie Bly herself.

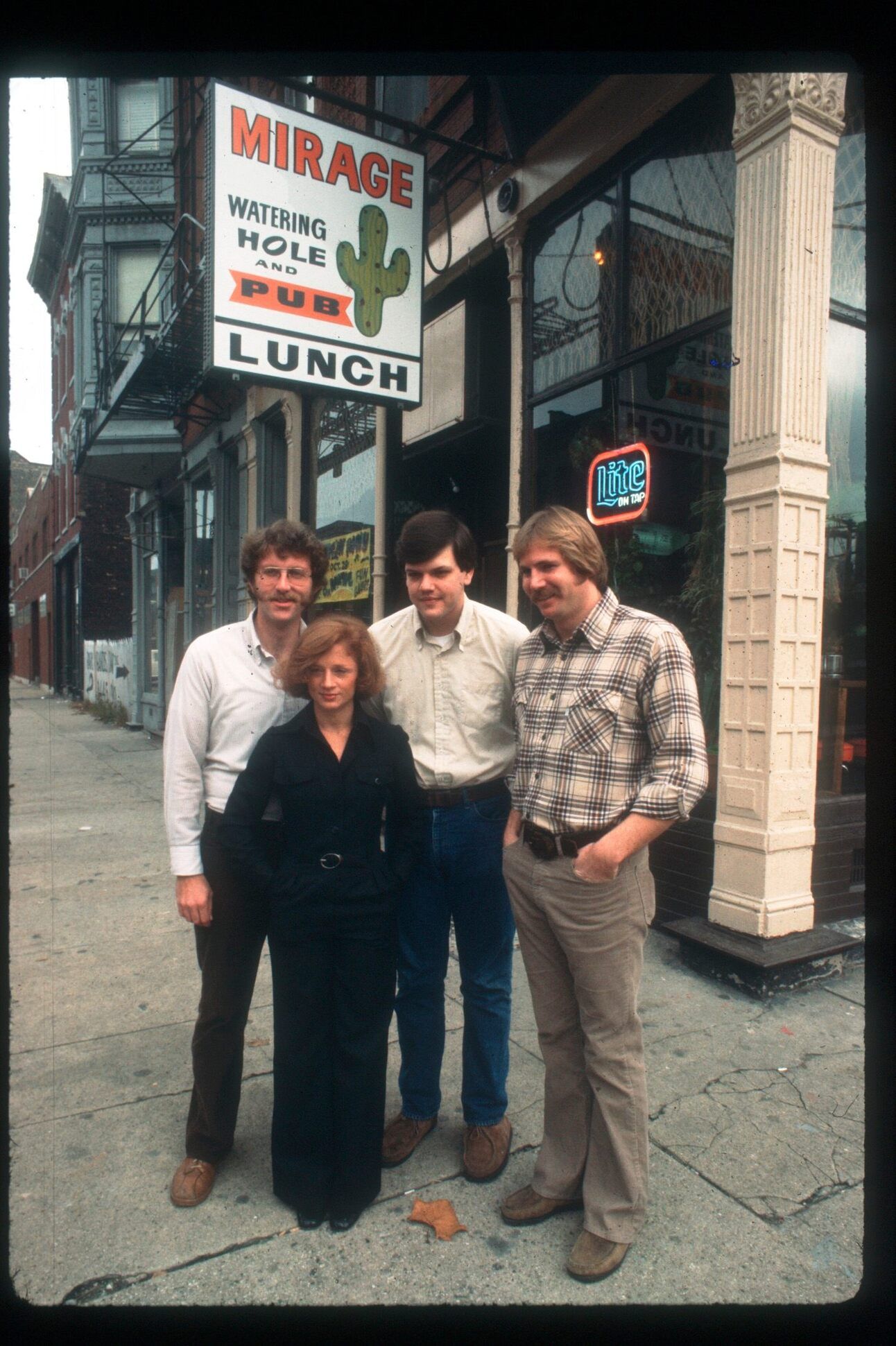

Pam Zekman at work inside the Mirage Tavern. When they bought it, the bar was literally falling apart. | Sun-Times file

Yet, if you haven't heard much about this story, it’s precisely because this investigation never gained the recognition it truly deserved.

In 1979, Zekman and the Chicago Sun-Times team became finalists for the Pulitzer Prize, but two influential jury members strongly opposed their nomination: Ben Bradlee, the legendary editor of the Washington Post since the Watergate days, and Eugene Patterson of the St. Petersburg Times.

In their view, undercover journalism and the use of false identities violated fundamental principles of transparency and journalistic honesty.

Bradlee was particularly categorical: “We instruct our reporters never to pretend to be someone they're not. Awarding this prize would have set journalism on the wrong path.”

Patterson went even further, claiming that the Mirage Tavern investigation had elements of “entrapment,” as if the journalists deliberately created conditions that encouraged officials to accept bribes.

The Pulitzer jury thus decided to send a strong and clear message: the ends don't automatically justify the means. The Mirage Tavern investigation, widely considered the clear favorite, was ultimately excluded for ethical reasons linked to the methods used by the journalists.

William Gaines, an investigative journalist who won two Pulitzer Prizes himself (first in 1976 with an undercover investigation, and then again in 1988 with traditional reporting methods), reflected bluntly on that decision: “It was a sensational story. It was such a great story and flying so high that everyone was saying, “Wow, can they give it two Pulitzers?” I guess the Pulitzer committee didn't want it taking over journalism, and that's why they stepped on its neck. That's one theory. They said, 'Let's get back to long gray type’.”

Gaines concluded, bitterly: "That was the end of undercover investigative reporting."

The long-term impact of that exclusion was severe. Major newspapers progressively abandoned undercover reporting, adopting increasingly restrictive ethical codes. Legal challenges multiplied, with defamation lawsuits often successfully targeting journalists specifically because they'd used deception.

Newspaper editors began asking themselves, “If an investigation like this can never win journalism’s top award and comes with so many risks, does it even make sense to pursue it?”

The End of Undercover Journalism?

Today in the United States—the very country that invented undercover reporting—this type of journalism has been relegated to a second-class status, if not worse.

Major newspapers, from the New York Times on down, explicitly forbid their journalists from using undercover methods. Even at the Columbia Journalism School—one of the most prestigious journalism schools in the world, founded by Joseph Pulitzer (the same editor who commissioned the legendary Nellie Bly to conduct history’s first great undercover investigation)—this method is viewed with deep suspicion.

We, however, firmly believe that undercover journalism still has a lot to say.

That’s exactly why we’re here.

But we’ve probably already talked too much for today.

Until the next Debrief,

Sacha and Luigi

WHO WENT UNDERCOVER RECENTLY:

📍 Austria

Activists from the anti-Zionist Jewish collective in Vienna recently went undercover to meet with Israeli Ambassador to Austria, David Roet. They documented some of his statements denying Israel’s intentional killings of babies and advocating for the execution of Palestinian minors involved in armed conflicts.

Source: The Skwawkbox

📍 UK

An undercover investigation by BBC Africa Eye exposed how fraudsters in the UK were selling fake sponsorship certificates to African migrants seeking employment, leaving them in debt and without protection. A network of exploitation built on desperation, documented through undercover methods.

Source: BBC Africa Eye

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at:

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply