- Debrief - The undercover dispatch

- Posts

- When leaks and whistleblowers were considered worse than undercover reporting

When leaks and whistleblowers were considered worse than undercover reporting

Because telling the truth has always been an act of disobedience.

In contemporary journalism, especially in the United States, the undercover method is often discredited based on a now-codified list of alleged violations: the use of deception, lack of transparency, and absence of ethics. As we explained in one of the first issues of Debrief, these criticisms don’t come out of nowhere—they stem from a long history of ostracism, mistrust, and discouragement toward the most intrusive and uncomfortable forms of investigative journalism.

In this newsletter, however, we want to take a step back and recall a time when even two tools that are now considered essential to investigative reporting—leaks, meaning the extraction of documents of public interest, and whistleblowers, that is, internal sources who expose secrets from within a closed system—were attacked using arguments surprisingly similar to those now used against undercover reporting. Same accusations, same tone, same attempts at delegitimization—not only from those in power, but from other journalists as well. The difference is that over time, in these cases, something has changed.

This issue was written by Luigi and edited by Sacha.

In This Issue of Debrief:

Pentagon Papers and Watergate, before the glory

Until not too long ago, the idea of publishing classified documents leaked by anonymous sources (so-called leaks) or relying on whistleblowers who revealed corporate or state secrets was far from a given or universally accepted practice. If today we consider these two tools an essential part of every good investigative journalist’s proverbial toolbox, it takes only a shallow dive into history to find serious accusations leveled at reporters who used these methods—accusations that described their work as outright acts of “treason.” So much so that even the two investigations most famously associated with these tools—the Watergate scandal and the Pentagon Papers—were not spared.

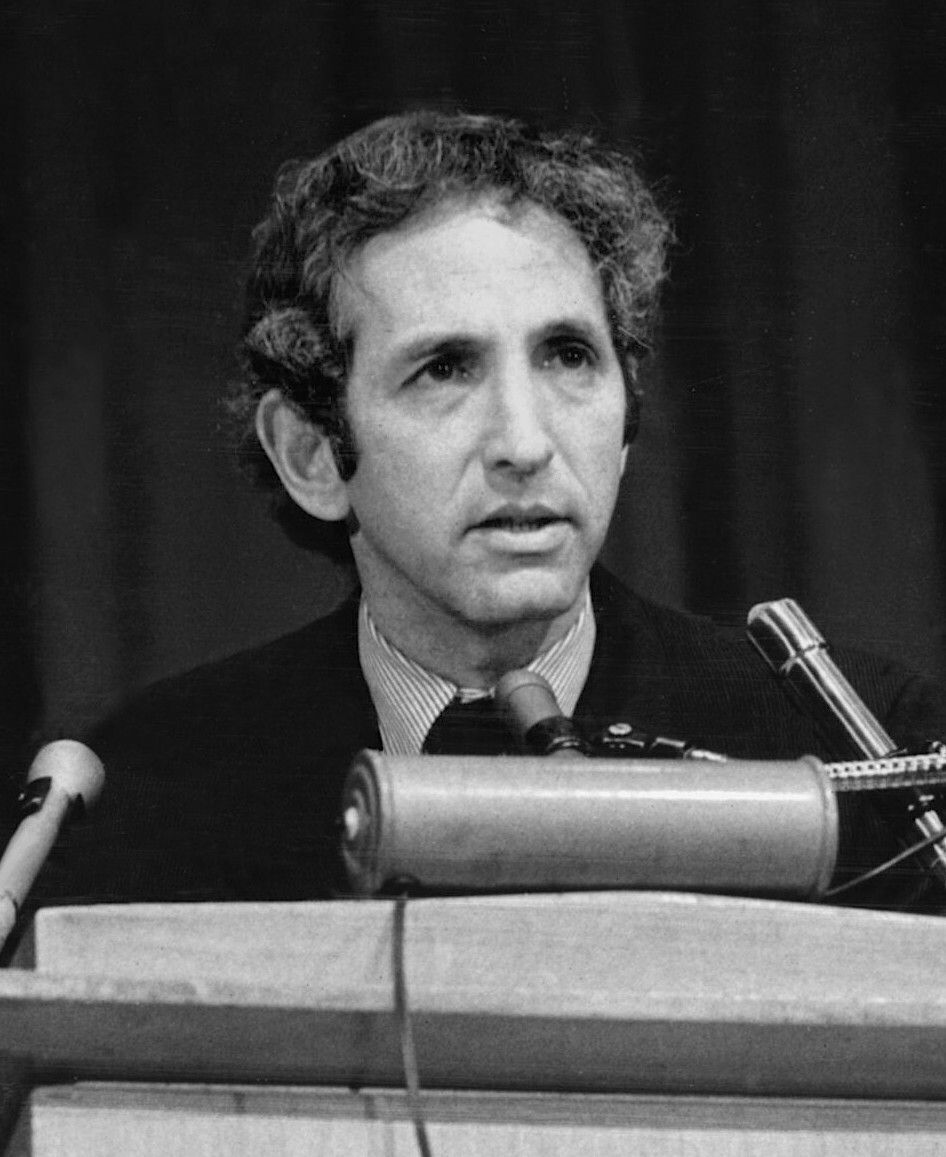

One of the first major leaks in history was that of the Pentagon Papers, classified documents on the Vietnam War that were delivered (as later emerged) by official Daniel Ellsberg to The New York Times and published in 1971. The release of the investigation caused an uproar. General Lyman L. Lemnitzer, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in an interview with The Scranton Times in July 1971, labeled Ellsberg, the source of the Pentagon Papers, a traitor, accusing him of ignoring the consequences of his actions on national security: “[Ellsberg] had committed a ‘traitorous act’ and didn’t know what he was doing to the security of the United States.”

Daniel Ellsberg

The Nixon administration tried to stop the publications by suing the newspapers in court. Even a Supreme Court Justice, Harry Blackmun, while admitting there was no “grave and irreparable danger” to justify censorship, warned that if the release of the Pentagon Papers resulted in war deaths or harm to allies, “then the Nation’s people will know where the responsibility for these sad consequences rests.” Some fellow journalists also voiced concerns: at a 1971 conference, Martin Hayden, editor of the Detroit News, said, “If every pamphleteer could publish a plan of a secret submarine or a list of foreign agents abroad, obtained from any peddler of secrets, I don’t think the public would stand for it.”

Only the following year, in 1972, The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein conducted the Watergate investigation, revealing the wide-ranging illegal activities orchestrated by President Nixon, thanks in part to information from an anonymous government informant known as “Deep Throat.” Even in that case, at the height of the investigation, the White House responded with hostility. Clark MacGregor, director of the Committee to Re-elect the President (CREEP), stated in October 1972, attacking The Washington Post by comparing its credibility to the low credibility of Democratic candidate George McGovern. A climate of suspicion surrounded the use of anonymous sources: some questioned the reliability of news based on secret information, and others even claimed that Deep Throat was a near-fictional character.

Yet, public opinion eventually came to recognize the extraordinary value of those investigations. The Pentagon Papers and Watergate went on to become iconic models of investigative journalism, still used today as benchmarks and sources of legitimacy for any inquiry that challenges public power. In media language, the suffixes “-gate” and “-papers” have, over the decades, become a kind of quality seal for stories destined to shape public debate: just think of Iraqgate, Datagate, Qatargate, or the Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, Cyprus Papers.

Assange and Snowden, in the crosshairs of democracy

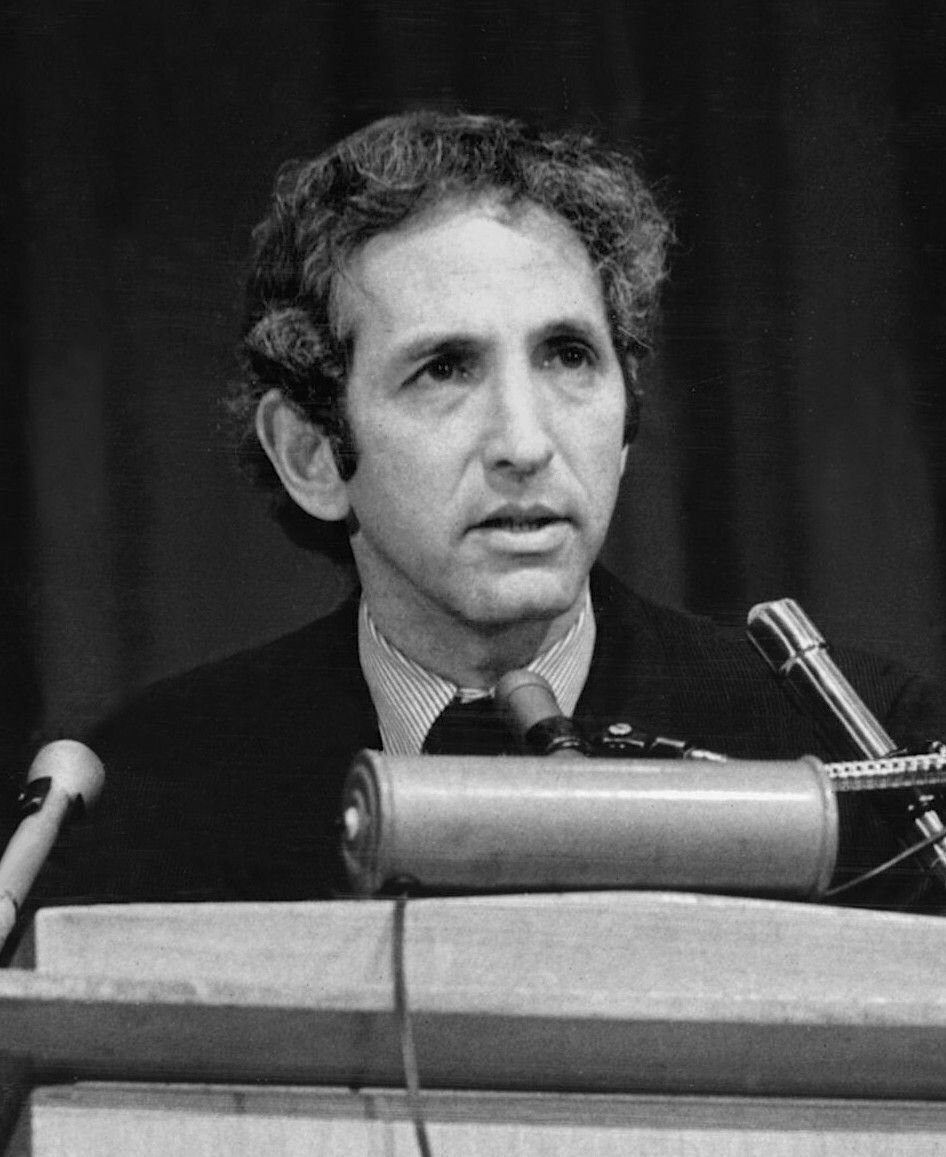

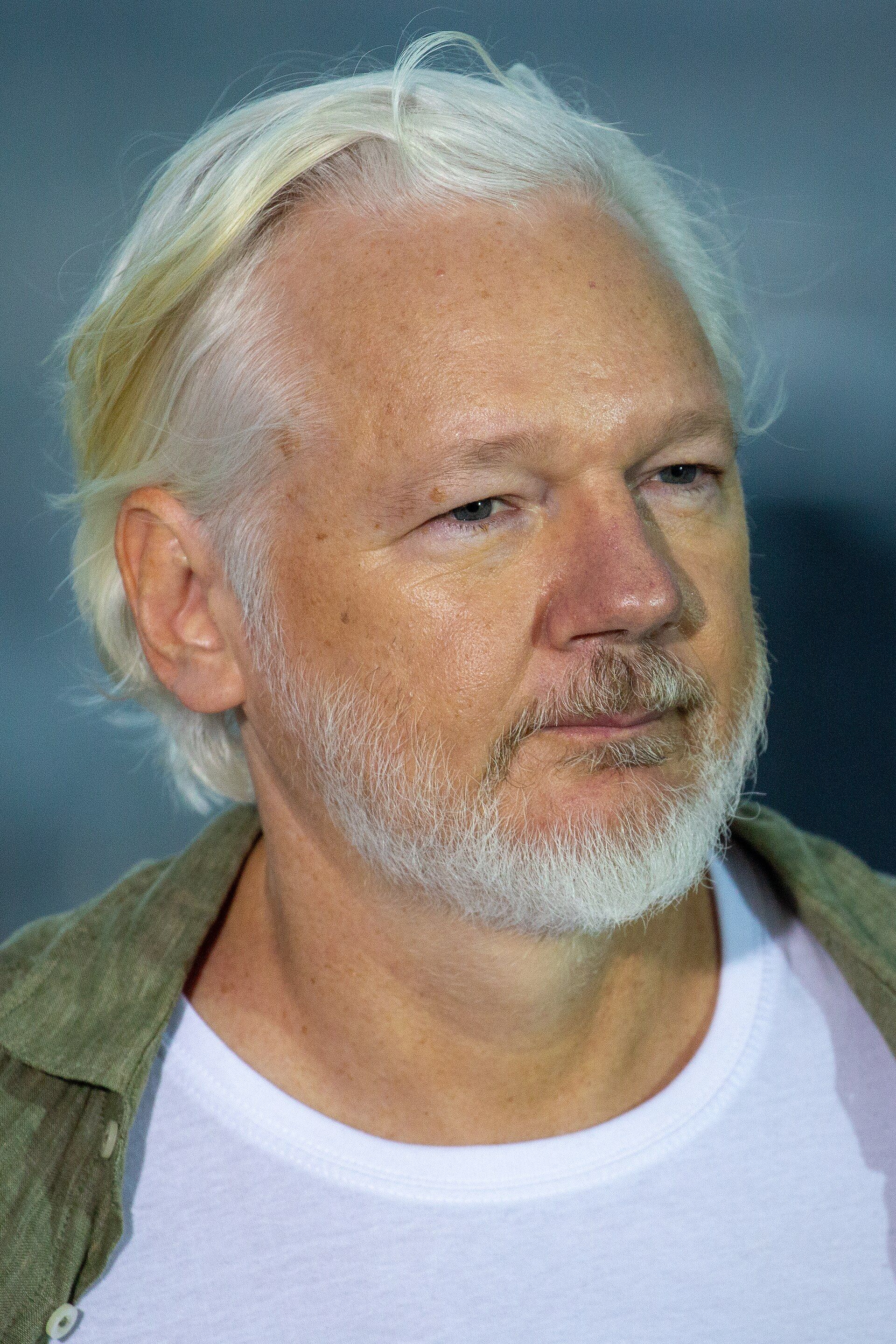

In the 2010s, forty years after the Watergate scandal and the Pentagon Papers, two other notable investigations brought the ethical debate over leaks and whistleblowers back to the forefront. Perhaps the most emblematic case is that of WikiLeaks, the platform founded by Julian Assange to publish classified documents anonymously. In 2010, WikiLeaks released hundreds of thousands of confidential files: from the “Collateral Murder” video showing the killing of civilians in Iraq, to the war logs of the Afghanistan and Iraq wars, to 250,000 U.S. diplomatic cables (the so-called Cablegate, provided by the analyst and whistleblower Chelsea Manning). The media impact was enormous, as was the outraged reaction from many governments and commentators. High-ranking U.S. officials denounced WikiLeaks in the harshest terms: Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called the release of the cables “an attack not just on the United States but on the international community,” claiming it endangered innocent lives and sabotaged peaceful relations between nations. The Obama administration described it as a “criminal act” and implemented measures to prevent future leaks. Numerous politicians accused Assange of irresponsibility; some, like Sarah Palin, even questioned why he wasn’t being hunted with the same urgency as Taliban or Al Qaeda operatives.

Julian Assange

The ethical concerns extended to journalists and analysts themselves. Some praised WikiLeaks for its radical transparency, but others harshly criticized it: Was this journalism or not? For example, Steve Coll, a well-known investigative journalist and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner, stated unequivocally that the massive leak of classified military documents was “unethical.” An editorial in The Atlantic argued that Assange appeared to be wielding a weapon to brandish rather than merely running a portal, lamenting the publication of too much unfiltered information at the risk of compromising security. WikiLeaks and its founder, Julian Assange, were broadly depicted as irresponsible, sensationalist, and potentially immoral.

Another telling example of this phenomenon is the massive leak of NSA documents by Edward Snowden. When, in June 2013, The Guardian revealed Snowden’s identity—he was a 29-year-old former CIA technician—and began publishing his shocking evidence of mass surveillance in the U.S. and worldwide, the immediate reaction was polarized. Politicians across the political spectrum painted him as a “traitor” to the nation and competed to condemn him for exposing national security secrets, calling for his head. Even the most progressive newspapers did not hold back. In The New Yorker, legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin stated he was no hero at all and called him “a grandiose narcissist who deserves to be in prison.” At the same time, New York Times columnist David Brooks described him as a loner representative of that “growing share of young men in their 20s who are living technological existences in the fuzzy land between their childhood institutions and adult family commitments.”

The Price of Truth

Despite growing public recognition of the value of leaks, many whistleblowers have paid—and continue to pay—a steep human, legal, or professional price for their revelations. Legitimacy often comes late and rarely translates into clemency. Edward Snowden, for example, still lives in exile. Having taken refuge in Russia in 2013 to avoid espionage charges in the United States, he has seen his disclosures fully confirmed over the years. Yet, despite this moral victory, he remains stranded overseas, denied asylum in any Western democracy and still wanted by his country (which continues to seek his prosecution under the Espionage Act, preventing him from invoking the public interest defense).

A similar—if not worse—fate has befallen other whistleblowers. Chelsea Manning, the U.S. Army analyst who released classified documents on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, was sentenced to 35 years in military prison. She served seven of them—a duration that was still “longer than any whistleblower in U.S. history.”

Chelsea Elizabeth Manning

Julian Assange, who published those documents, paid an even higher price. For the first time in history, the United States charged a publisher with violating espionage laws for disseminating state secrets. If extradited, Assange faced up to 175 years in prison, in solitary confinement. In the end, in 2024, after a plea deal, he was released. His case shows how, despite the retrospective acknowledgment of the public utility of leaks, legal mechanisms still often treat whistleblowers and the journalists who work with them as criminals.

Many others could testify to having sacrificed their careers, freedom, or mental health to bring uncomfortable truths to public attention—from Daniel Ellsberg, prosecuted for the Pentagon Papers (and recently passed away as a rehabilitated icon of whistleblowing), to more recent figures like Reality Winner and Daniel Hale, young analysts who were imprisoned for exposing, respectively, Russian interference in the U.S. elections and the secret drone program. All of them ultimately paid a very high price.

But in all of this history, one thing remains the most troubling: those who discredit, accuse, and condemn those who break the silence are not only governments, who have an interest when the press exposes their wrongdoing. They are also—and above all—those journalists who hand out credentials of legitimacy, who decide what counts as journalism and what doesn’t, who criticize the means, regardless of the public value of the findings. They do it for a thousand reasons: cowardice, caution, competition, political or corporate interest. But the result is always the same. A slow and relentless silencing of information. Because if undercover reporting can’t be used because it involves deception, if leaks can’t be used because they violate state secrets, if whistleblowers are suspect or attention-seeking, then how will we do the next investigation?

Until the next Debrief,

Luigi and Sacha

If you've come across an undercover investigation you think we should feature, share it with us here:

👉 https://forms.gle/1JbqMBJUfoRU9MBp7

If you have suggestions, questions, tips (or insults), drop us a line at:

👉 [email protected]

If you enjoyed this newsletter, pass it along to your friends using this link:

👉 https://debrief-newsletter.beehiiv.com/

Follow us on Instagram, occasionally we'll upload content different from the newsletter:

👉 https://www.instagram.com/debrief_undercover/

We've also launched a podcast featuring interviews with the authors of memorable undercover investigations:

👉 https://open.spotify.com/show

And if that's still not enough, join our Telegram channel, where we can keep the conversation going:

👉 https://t.me/debrief_undercover

Reply